Archives Spotlight: The Hollywood Bandit

“I don’t want any bait bills or dye packs, got it?”

“I don’t want any bait bills or dye packs, got it?”

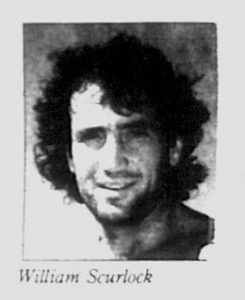

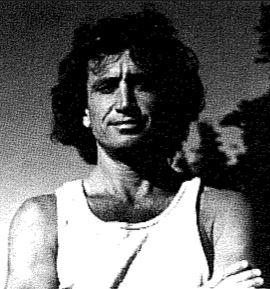

Scott Scurlock, known to police as “Hollywood,” clutched a black pistol. He didn’t point the gun at anyone. He didn’t wave it around. But he made sure everyone knew he had it as he confidently made simple demands.

Heeding Scurlock’s warnings, a bank teller escorted the robber to the vault, while two henchmen manned the lobby.

Within minutes, Scurlock wielded a duffle stuffed with over a million dollars, and the trio of thieves slipped out of the Lake City, Seattle branch of Seafirst National Bank and into the dark, stormy Thanksgiving eve of 1996.

Chaos ensued.

Let’s go back a few years.

William Scott Scurlock was born to a teacher and a preacher in Virginia. He was a smart kid, but lacked motivation and didn’t bother himself much with academics. His childhood friend, Kevin Meyers, went off to the University of Hawaii, where he would learn he lacked academic motivation as well. Scurlock moved to Hawaii in 1974, and within a couple years, found himself living with Kevin — by then a college-dropout — on a tomato farm where they worked together.

One day, the two young men stole a few small marijuana plants from a neighboring farm and easily sold the loot. They suddenly realized how to make a lot of money without much work (or regard for the law) and planted their own hidden stash. The pair would soon get themselves fired and kicked off the farm upon the landlord’s discovery of the growing marijuana.

Scurlock moved to Olympia and enrolled at Evergreen State College in 1978, with aspirations of becoming a doctor. He grew obsessed with the sciences, and began sneaking into the chemistry lab after hours. One rumor says he snuck in through the ceilings. Another rumor says he convinced security guards that he was a professor, Frank Abagnale-style. Either way, he successfully snuck into the lab repeatedly to cook methamphetamines, which he got away with long enough to rent, and eventually purchase, several acres only minutes from Evergreen.

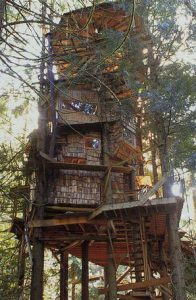

On the new property, he cooked drugs in the barn and built a treehouse that looked like something out of a fairy tale. The treehouse had three stories of indoor living, a deck wrapped around the base, another deck at the top, a 60-foot stairway, a large fireplace and an outdoor bathing area, complete with plumbing and electricity. Scurlock claimed that he and the group of friends, whom he branded his “tribe,” built the compound in two weeks because the drugs kept them awake and busy day and night. It actually took several months, using material they gradually stole from a nearby lumberyard.

Kevin’s brother Steve Meyers moved to Washington to help Scurlock complete the treehouse due to his expertise in design. Scurlock also hired longtime friend Mark Biggins to do some work—perhaps out of pity, for Biggins was broke. Both men would eventually become integral partners in crime.

Living like a rich lost boy, Scurlock smuggled chemicals from the Evergreen labs and sold drugs for over a decade before his primary amphetamine distributor was murdered in 1990. The violence scared Scurlock straight (temporarily) and completely dropped out of the drug business.

He must have had a lot of savings from his drug enterprise, because it was over two years before Scotty Scurlock would dive into his next venture: bank robbery.

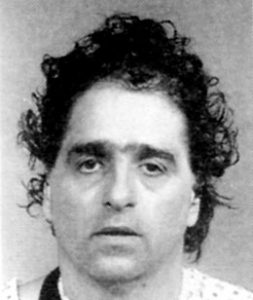

In June 1992, Scurlock enlisted the help of Mark Biggins to rob the Seafirst Bank in Madison Park. Biggins persuaded his girlfriend to drive the getaway. Steve Meyers declined to participate in the robbery, but he agreed to launder the money through Las Vegas casinos.

Without giving a real reason, Scurlock asked another friend to receive a few shipments on his behalf. The friend agreed and unwittingly became an avenue for Scurlock to obtain high-quality theatrical makeup, which he wore during robberies. In the first instance, he wore a prosthetic nose and heavy color application. Apparently a fan of Point Break, Biggins wore a rubber Ronald Reagan Halloween mask. The two men walked into the bank and aggressively announced their presence and barked orders to intimidate witnesses, a tactic called the “take-charge” method. No shots were fired. They left within minutes, and didn’t bother with the vaults. Nobody got hurt, and they left Seattle about $20,000 richer.

Scurlock was elated. Biggins, not so much. While Scurlock loved the adrenaline rush, Biggins and his girlfriend were terrified. Apparently the getaway did not go as smoothly as Scurlock would lead others to believe. One account says the getaway car was stolen from a bank customer, and the engine flooded when they tried to leave, forcing the crew to flee on foot. What really happened remains unclear.

Unfazed, Scurlock went at it alone the next time, two months later, when he walked into the Seafirst Bank in Madison Park. Yes, he robbed the same bank twice in a row. This time, his disguise was different, but the employees, and the FBI and police who reviewed the surveillance, recognized his demeanor and method.

At first, law enforcement dubbed him the “Take Charge Robber.”

With at least four more robberies that used at least four more disguises, Scurlock accumulated over $320,000 in 1992 alone, including $252,000 from the last one of the year. The FBI and police started calling him “Hollywood.” The press insisted on “Hollywood Bandit.” After the quarter-million-dollar score from the Hawthorn Hills Seafirst Bank, Hollywood and his crew would take a yearlong break.

Scurlock spent a lot of money around town, but mostly gave away the money to environmental causes. He thought he was Robin Hood. At the end of 1993, Spurlock coerced Steve Meyers back into the fold and recruited him to help with the next robbery. They doubled down on the Hawthorne Hills location, getting away with another $100,000.

The FBI was able to use the amount taken in each heist to predict the date of the next. They were fairly accurate in their estimations, but could not quite pin down the location of the future heists, despite widespread lookouts. Unbeknownst to him, Hollywood was almost caught during several robberies from 1994 to 1996.

On the night before Thanksgiving, 1996, Hollywood robbed his last bank.

Rain was pouring down, whipped by strong winds, just 19 minutes before closing time at Seafirst Bank in Seattle’s Lake City. The evening’s last flurry of customers stood in the bank, preoccupied with getting home or wrapping up holiday errands. Hollywood and his crew marched into the bank, spent about four minutes inside and walked out with their largest take to date. As they exited, they instructed everyone to stay on the floor until police arrived.

A teller had recognized the robbers and hit the silent alarm as soon as Hollywood first arrived in the bank. Police still didn’t arrive before the robber fled, but they had gotten a key head start.

One of the bank’s customers disobeyed Hollywood’s orders and followed them after they left. The customer described the getaway car to police. This should have aided in capture, but once again, Hollywood was a step ahead. Not far from the bank, his crew had ditched the getaway car and switched to a white van.

So, what finally got them caught?

Seattle rush hour. It was 6 p.m. the day before Thanksgiving, and they were trying to go south from North Seattle. Even this, they nearly got away with. But onlookers noticed a white van with flashlights waving about the inside of the van as the robbers frantically searched for bait bills and dye packs.

A police pursuit ensued. The Puget Sound Violent Crimes Task Force eventually outflanked the van enough to force it to stop. Hollywood got out of the driver’s seat and did something he’d never done in his previous adventures in drug dealing or robbing banks. He fired his gun. He shot at the police, and the police shot back, but they could not shoot him.

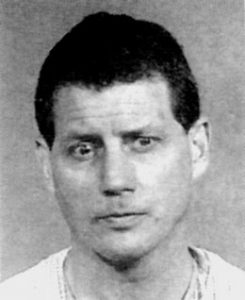

Somehow, Hollywood managed to get the van into gear, sending the van barreling into the front of someone’s house. The police approached to find Meyers and Biggins with non-fatal gunshot wounds. Scurlock left them behind and fled. Also in the van were several firearms and the bag full of cash, but police didn’t find Hollywood or his pistol. Again, the search was prolonged.

With a brutal storm coming down, several branches of law enforcement combined efforts and conducted a full-scale manhunt all through the night.

One of many homes the police visited that night belonged to Wilma Walker. They searched her yard, found nothing, and moved on. For some reason, they did not search the decommissioned, 10-foot camper on her property. Well, Wilma, who was 85 years old, had her sons, Robert and Ronald Walker, over for Thanksgiving dinner the next afternoon. They knew about the manhunt, and they heard about a $50,000 reward offered by the victimized banks.

Ronald was able to get a peek inside the camper to see someone was inside. Someone who, from a glance, matched the description given by police.

Within minutes, the camper was surrounded by police. One officer sidled up to one of the curtained windows trying to hear or see something. He banged on the camper. No response. He tried to unlock the door.

BANG! A gunshot went off.

The police opened fire on the camper. When firing ceased, there was no sign Hollywood was still alive. There was no assurance he was dead or injured, either. They sat and waited. Eventually they bombarded the camper with tear gas and forced entry. Turns out the only shot Hollywood had fired was aimed at himself. He was found dead on the camper floor.

Scurlock robbed 17 banks of $2.3 million, making him one of the most prolific bank robbers in U.S. history.

The FBI searched Scurlock’s property and found an arsenal, evidence of extensive travel plans, a secret, underground room where Hollywood stored all of his disguises and makeup, and tons of cash stored away and buried in the yard.

The Walkers eventually collected $60,000 in reward money after it was initially denied by the banks on a technicality. Thanks to media and public backlash, the banks were pressured into issuing the reward money.

Steve Meyers and Mark Biggins each faced state and federal charges. Both were sentenced to 21 years in federal prison. Meyers was released in 2013, Biggins in 2015.