Spotlight on State Library Special Collections: The Holy Roman Emperor, the Conquistador, and the Emperor of the Aztecs

Recently a question hit the State Library Twitter feed that requires a little more explanation than Twitter’s 280-character limit allows. That very fine question was: “What is the oldest book in the library’s collection?”

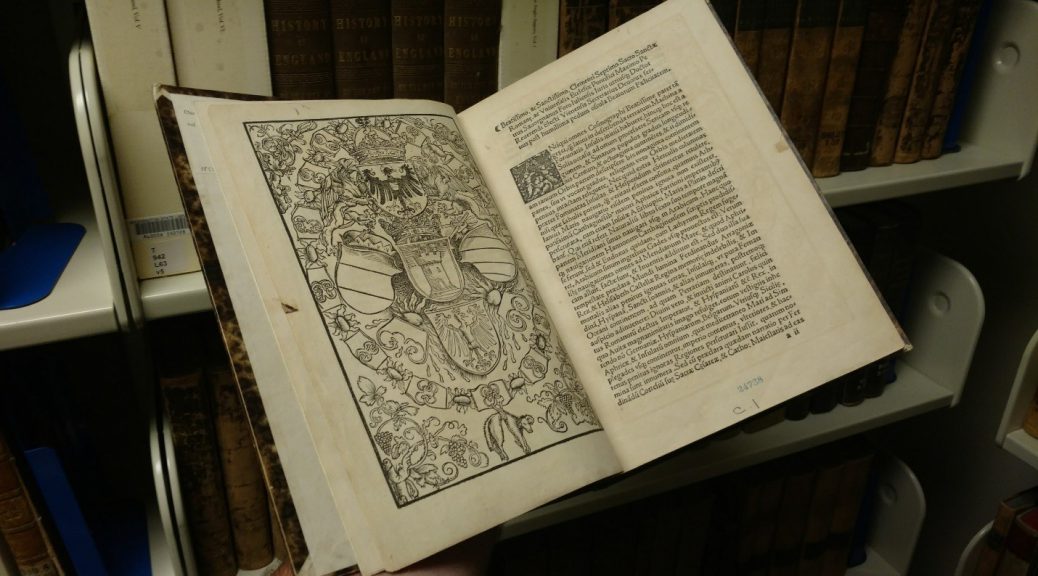

Well, the State Library has a lot of older books and maps in our Special Collections, but the Territorial Collection has the distinction of holding the oldest book.[i] It also happens to be amongst the earliest European accounts about the Americas: it is the first Latin edition of the second letter from Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to Hapsburg Emperor Charles V, the King of Spain.

The letter is dated Oct. 30, 1520, but was translated into a Latin edition from the original Spanish issue by Petrus Savorgnanus and published by Fredericus Peypus in Nuremberg in the year 1524. It has an immensely unwieldy title (forgive me if I get one of the words wrong):

Praeclara Ferdinādi Cortésii de noua maris oceani Hyspania narration sacratissimo ac inuictissimo Carolo Romanorū imperatori semper Augusto, Hyspaniarū, &c̄ regi anno Domini M.D.XX. transmissa: in qua continentur plurima scitu, & admiratione digna circa egregias earū p[ro]uintiarū vrbes. In colaru mores, pueroru Sacrificia & Religiosas personas, Potissimu [que] de Celebri Ciutate Temixtitan Variis [que] illi [con] mirabilis [con], que legete mirifice delectabut.[ii]

What a mouthful![iii]

In this letter, Cortés apologizes for not getting back to the Emperor sooner, boasts of his deeds in the new world as he claims it for the glory of Spain, and describes vividly the Mexica people of the Aztec empire, their impressive buildings, and distinctive practices. He also recounts how he dealt with dissenting explorers on his crew who attempted to thwart his conquest, perhaps being under the influence of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, whose orders to stay in Cuba rather than embark on an expedition to Mexico, Cortés had disobeyed.

Of Velázquez, Cortés has little good to say.

In contrast, Cortés offers significant praise for “Muteczuma,” which is the spelling he gives to Moctezuma II, the “Emperor” (Ninth Tlatoani, actually) of the Aztecan Empire. This is partly due to Moctezuma’s willingness to comply with the aims of this conquistador, but also due to the grandeur and extent of his domain and Cortés’ awe regarding the people’s submission towards this ruler.

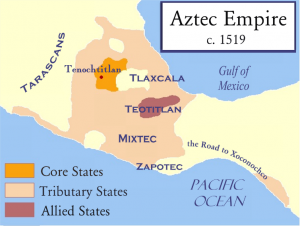

Cortés describes the Aztec Emperor’s palaces in Tenochtitlán as filled with copious domesticated birds nestling at engineered saltwater and freshwater pools, exquisite gardens, gifts and tributes from across the kingdom (which stretched as far as the northwestern part of modern-day Guatemala), and — of special note — men, women and children who were born with congenital disorders such as short stature, gigantism, albinism, and spinal deformities (kyphosis), who had their own reserved areas in the palace complex with dedicated “keepers.”

It is commonly thought that Moctezuma kept these people nearby as talismans to shield him against supernatural forces. This supposed quality was ultimately insufficient.

While their initial meetings between Cortés and Moctezuma were cordial, the ruler was taken hostage within two weeks and forced to pledge allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor. The Aztecs briefly rose up after the Spanish disrupted a sacrificial rite. The ruler was denounced and replaced after attempting to pacify his people.

Shortly afterwards he was struck to death with a rock by his own subjects for his perceived weakness. Cortés, his Spanish soldiers, and the neighboring Tlaxcalan people who had resisted Aztecan domination are then driven out of the capital city to nearby Tacuba, an event known as La Noche Triste. The letter closes with Cuitláhuac, Moctezuma’s brother, ascending to the throne — a promotion that lasts a mere 80 days — and Cortés’ solemn pledge to the emperor that he will recover control over the situation.

In Cortés’ third letter he follows up with how the Spaniards and their allies reestablished the upper hand at the Battle of Otumba, then returned to conquer Tenochtitlán and ultimately brought the empire to devastation. The Spanish essentially razed the ancient city to establish the capital of New Spain, building what is now known as Mexico City, atop the ruins. Although there is evidence that our copy of the second letter once was bound with the third letter, the state library has never had a contemporaneous edition of that letter in the collection.

Speaking of the library’s copy, let’s step away from all that bloodshed and return to the book as an object. The library’s copy of the book was rebound in the 19th century. Sadly, our copy lacks the first published map of Tenochtitlán (online and pleasantly colored at https://www.historytoday.com/kate-wiles/map-tenochtitlan-1524) that is sometimes included with the second letter, and it lacks the woodcut portrait of Pope Clement VII (a fine copy that collates with our copy can be viewed online courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library). These often were “lost” or more likely removed for other purposes during re-binding. Our copy does, however, have the crest of Charles V. (pictured below)[iv]

Another narrative published in Basel in 1521 that recounts the discovery of the West Indies and its people has been included at the end of the bound title as practical substitute for Cortés’ first letter that had long presumed to have been lost.

De rebus et insulis noviter repertis a Sereniss Carolo Imperatore et variis earum gentium moribus,[v] written by the Italian historian Pietro Martire d’Anghiera (b. 02/1457; d. 10/1526) was first published in Basel, Switzerland in the year 1521.

Regarding the status of Cortés’ first letter, a 1908 article on the English translation of the five letters of Cortés from British Journal, The Spectator states, “a duplicate was discovered by [English historian] Dr. [William] Robertson (whether it is identical with the letters actually sent by Cortés is doubtful; but the two were intended to be mutually corroborative).”[vi]

You can read an English translation of the 2nd letter at the Early Americas Digital Archive at the University of Maryland.

A two-volume work translating the five letters that Cortés wrote to Charles V into English can be found at Archive.org. Volume One deals with the first two letters, while Volume Two handles the third, fourth, and fifth letters.

[i][i] As noted in “Governor Isaac I. Stevens and the Washington Territorial Library” by Hazel E. Mills, The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 1 (Jan., 1962), pp. 1-16: “Another interesting work in the collection is the Bellum Christianorum principium of Robertus Monachus, printed in Basle (Basel?) in 1533. Stevens must have purchased it for the reprint (that) it contains of the text of the Latin translation by Alexander de Cosco of the letter Columbus wrote in 1493 to Gabriel Sanchez, or Sanxis announcing his discovery of the New World. This is the edition from which most of the early writers quote. The copy of the work in the Territorial Library collection collates with the copies described in the (Catholic) Church and John Carter Brown catalogues.” (Mills, pg. 11)

[iii] Actually, the full title is a bit longer, given the translator’s marks at the end: Praeclara Ferdinādi Cortesii de noua maris oceani Hyspania narration sacratissimo ac inuictissimo Carolo Romanorū imperatori semper Augusto, Hyspaniarū, &c̄ regi anno Domini M.D.XX. transmissa : in qua continentur plurima scitu, & admiratione digna circa egregias earū p[ro]uintiarū vrbes. In colaru mores, pueroru Sacrificia & Religiosas personas, Potissimu[que] de Celebri Ciutate Temixtitan Variis[que] illi [con] mirabilis [con], que legete mirifice delectabut.

p Doctore Petru saguorganu Foroluliense Reun. D. Ioan. de Reulles Episco. Vienesis Secretariu ex Hyspano Idi omate in latinuversa. Anno Dni. M.D.XXIII.KL.Martii: Cum Gratia, & Privilegio.

[iv] Again, per Hazel Mills, “The first occupation of Mexico City, the Noche Triste and the retreat to Tlascala . The Territorial Library copy collates with the copy described in the John Carter Brown catalogue which lacks the maps of Mexico but is followed by twelve numbered leaves containing Peter Martyr’s abstract of Cortes’ lost first letter, De rebus, et Insulis nouiter Repertis. On the verso of the last leaf of the De rebus is a clear impression of the title page of the third letter, indicating that it was once bound in the same volume. The leaf with the portrait of Pope Clement VII on the verso is missing; probably it was removed in an early rebinding, since there is only a slight impression of the leaf preceding, the present binding is of the 19th century.” (Mills, pg. 11)

[vi] http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/12th-september-1908/25/the-letters-of-Cortés-to-charles-v-translated-and-

— From the desk of Washington State Library Special Collections