Washington State Library honors Native American Heritage Month

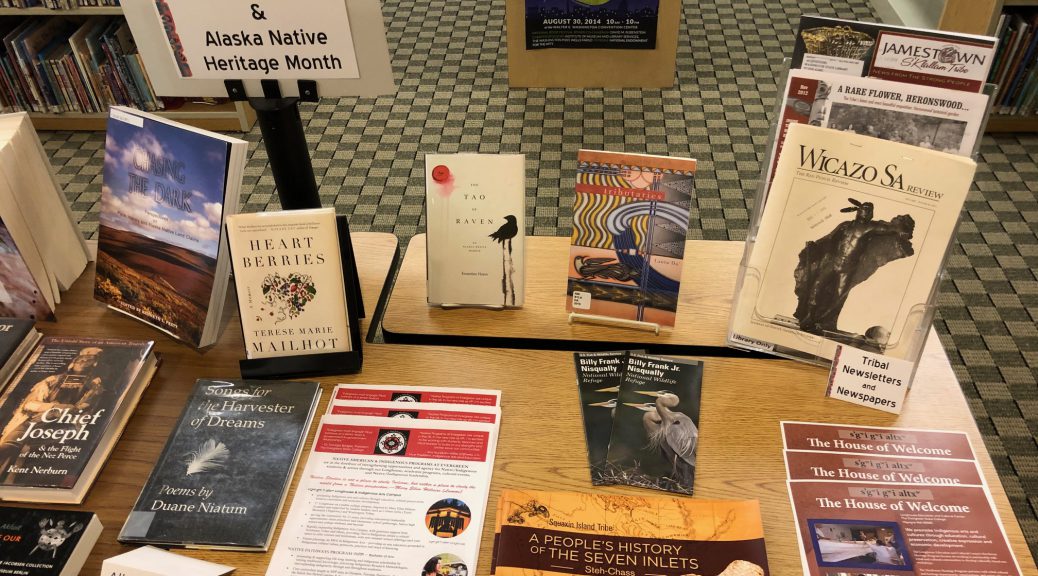

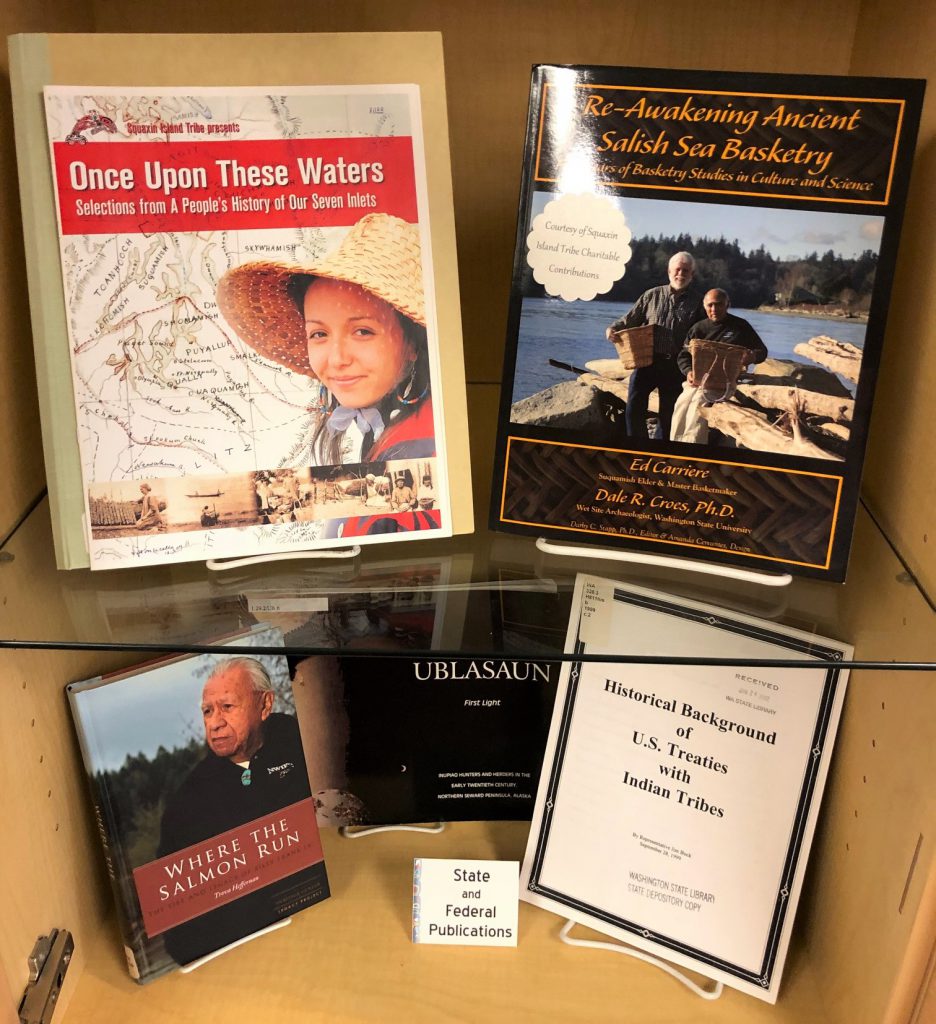

Earlier this fall, a team of WSL staff members worked together to create a few displays in the library to honor Native American Heritage Month.

As a state and a federal depository, the Library houses many documents of historical value and significance, such as tribal treaties and maps. Highlights from our Pacific Northwest collection include poetry, fiction and nonfiction by Indigenous authors as well as books on Native art traditions and artists. Many of Washington’s Indigenous communities also publish their own tribal newspapers and newsletters, and a selection of these publications is also available in the collection.

While working on these displays, Tien Triggs, Collection Maintenance Specialist of the Washington State Library, reached out to Charlene Krise, Tribal Elder and Executive Director of The Squaxin Island Museum, Library, and Research Center. The piece below is a result of their meeting.

In 1974, there were 175 members.

The Squaxin Island tribe, the People of the Water, numbered fewer than 200 in a year when a court decision upheld the traditional fishing rights laid out in the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854.

The Indian Child Welfare Act followed in 1978, ending the practice of state welfare agencies placing Native children in non-Native homes. That same year, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act recognized the right to exercise Native religious beliefs and practices, which had been a federal offense punishable by imprisonment since 1883.

Other legislation enacted in the decades afterward helped establish tribal governments, strengthen self-governance, and reclaim lands and cultural artifacts, but it would already be too late for the thousands of tribes that had been displaced by Congress’s Policy of Termination and Relocation in 1953. The Squaxin Island tribe had survived termination under this policy, but would the 175 tribal members still left in 1974 be enough to lay a strong foundation for the future?

According to tribal Elder Charlene Krise, Executive Director of the Squaxin Island Museum, Library & Research Center, the answer was yes. It was enough.

Today, tribal membership exceeds 1,000 and continues to grow. While it may seem unlikely that the traditional practices so necessary for sustaining tribal culture would have a place in this heavily technological world, the museum has embraced technology to educate and to create an online community for tribal members and beyond.

Staff at the museum have regularly served as adjunct faculty and taught online classes at Washington universities; the tribe also has a YouTube channel with videos demonstrating protocol and documenting their annual intertribal canoe journeys, as well as sharing other community events.

Technology has also made it easier for a widespread, intergenerational community to maintain strong cultural connections with each other, though it may never really replace some tribal traditions.

Stories and songs can be written down and recorded, thereby ensuring that the wisdom of the Elders can be preserved, but some knowledge is best passed from one generation to the next through hands-on experiences—canoe journeys, dancing, drumming, basket weaving.

At the heart of this effort to document Squaxin heritage is the museum, which houses tribal artifacts, as well as those uncovered at the Mud Bay archaeological site. The museum’s library has a diverse collection of titles and a research space and has even served as a resource for researchers from as far away as east Africa.

Every visitor is encouraged to ask questions, to discover the history, and to learn the stories of the Squaxin, the People of the Water. The knowledge here is invaluable, a testament to the unwavering commitment of tribal members to preserve their past for this generation and for the ones to follow.

In 1974, they were only 175. But it was enough.