A Rainmaker Meets His Match in Ephrata

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

The reel grabbed at random this week contained The Big Bend Empire, the first newspaper established in Waterville, Washington. The issue for May 13, 1920 included this intriguing article:

EPHRATA TO TRY OUT RAINMAKER

“The people around the Grant county seat want rain, and in fact they are willing to try any old scheme to get it, even to employing a professional rainmaker.”

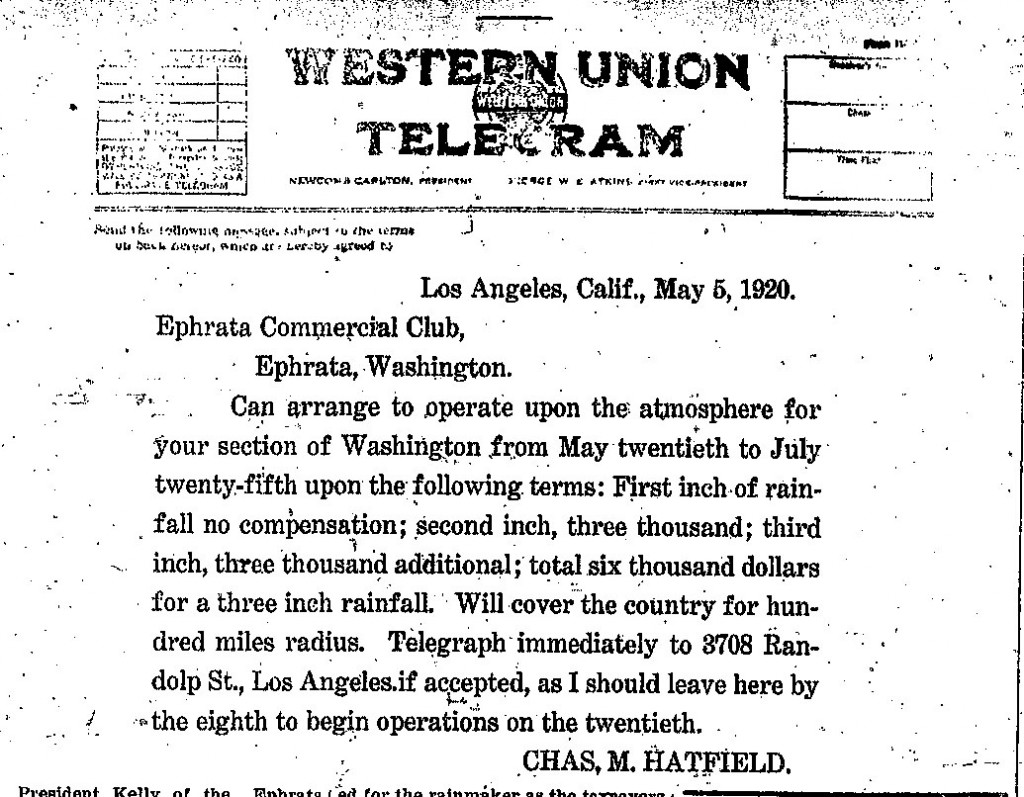

“The Ephrata Commercial Club has entered into negotiations with Chas. M. Hatfield of Los Angeles, who claims to have had success in rainmaking in other sections.”

“The fact that the commercial club of Ephrata became interested in Mr. Hatfield’s proposition made it possible to guarantee $6,000 to Mr. Hatfield. Under the contract with the Commercial club he is to receive for first inch nothing; for second inch $3,000; third, $3,000 additional with a time limit of June 10. We understand that Mr. Hatfield is now on the ground and busy with his experiments.”

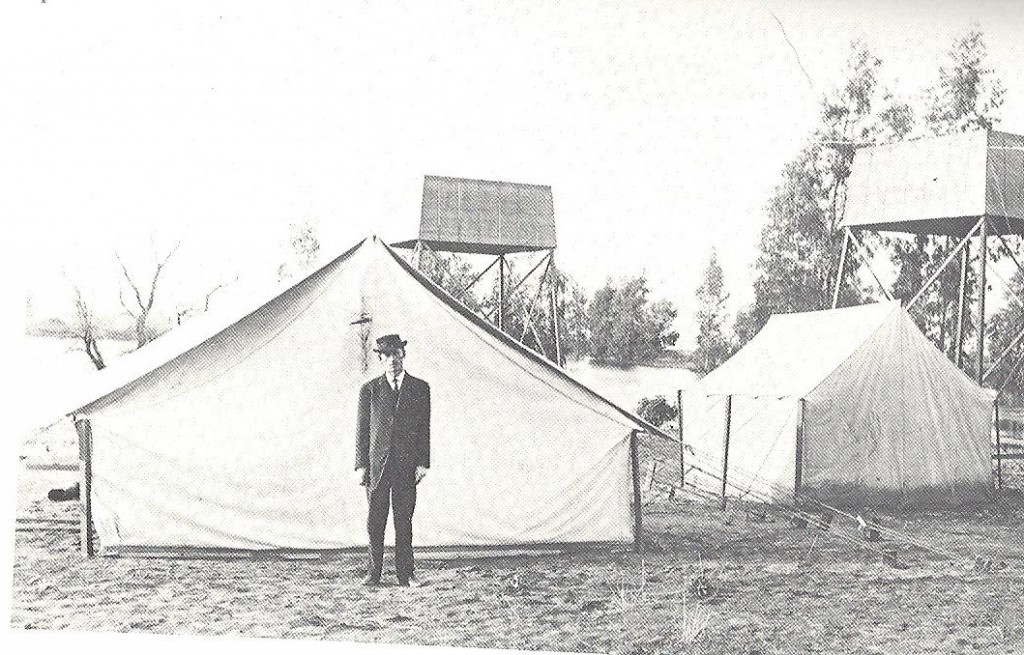

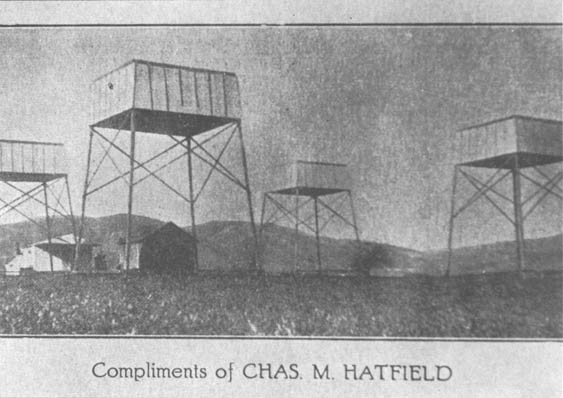

Charles Mallory Hatfield was already a famous figure throughout the West by 1920. The dapper 45 year-old sewing machine salesman had a strong resume, he claimed, of creating conditions which would result in rain for the parched corners of the world. His method included mixing a concoction of 23 chemicals (to this day the ingredients remain a secret) and setting this stew in vats atop 20-ft. high towers near bodies of water. Hatfield’s place in the history of “pluviculture” earned him an entire chapter in Clark C. Spence’s The Rainmakers (1980). One editor is quoted in this work on the odoriferous impact of Hatfield’s towers, writing they smelled like “a limberger cheese factory has broken loose … These gases smell so bad that it rains in self defense.” Electricity was also used in the process.

The rainmaker had set up his operation at the east side of Moses Lake and became an instant regional media sensation. He erected a tower constructed of 4 x 4s about 16 ft. square and over 20 ft. high, with vats containing his 23 top secret ingredients.

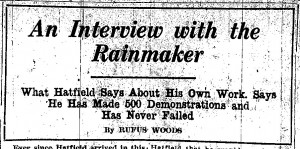

Sure enough, the area was rained on, but less than an inch. Weathermen pointed out that the distribution of the wet stuff was too vast to give any Hatfield any credit. They said the rainmaker took a long chance and won. But it was still far short of what the inventor promised. The Wenatchee World seemed to take a special interest in covering this story. After Hatfield’s June 10 deadline passed without reaching the desired goal, legendary World publisher Rufus Woods paid a visit to Moses Lake to conduct an interview.

Some of the rainmaker’s observations made during the interview concerning the Ephrata-Moses Lake area included:

“The conditions in this country are the hardest to make a showing in of any place I have been. When I get my forces at work, so often the wind comes up and blows them all away.”

“I have operated from Dawson to Mexico and Texas but this is the dryest atmosphere I have ever had to deal with.”

“It is harder to produce one inch here than it is five in California. I gave these people a better contract than I should have had I known the conditions in this locality.”

Hatfield also made a political prediction: “It is only a matter of time till the government will come to me … I know all these weather men poke fun at this. But they always tell what can’t be done when I am starting. It’s the same old hash, they go for me at the start. But results are what count. I have never failed to produce the record rainfall in every place I have operated.”

But fail he did at Moses Lake, and he quietly dismantled his tower, collected no fee, and set out for the next customer. His pluvicultural career was over by the 1930s. He died in 1958.

The U.S. government apparently never used his services. In fact the U.S. Weather Bureau made a point of highlighting Hatfield’s failures. During the Dust Bowl years Hatfield supporters could not convince the government to employ his methods.

But Hatfield did live long enough to see rain-making develop into a high-tech science both in cloud seeding and in warfare. If you look up the subject heading “Rain-making” in the WSL catalog, you will find many reports in state and federal publications.

The Big Bend Empire, which started in 1888, is an ancestor of the current Douglas County Empire Press. The entire run is available on microfilm, yes even via interlibrary loan, through the Washington State Library.