Newspaper Discussion: Preservation and Access Issues

From the desk of NDNP Coordinator, Shawn Schollmeyer: In our NDNP Office located in the basement of Suzzallo Library at the University of Washington we share this insight into the world of newspaper digitization and preservation by guest writer Casey Lansinger. Casey participated as an intern in our program and will be graduating with an MLIS in June 2013.

In July of 2012, I left my sunny and dry hometown of Denver, CO for wet and green Seattle. I suddenly found myself in a world where drivers are uncomfortably polite, the coffee is understandably strong and where this Colorado girl had to buy her first raincoat and pair of galoshes (yet still manages to get dripping wet with or without them). In Seattle, I would finish up my third and final year at University of Washington’s iSchool, where I am pursuing a Masters in Library and Information Science. My life in Denver, however, was all about journalism and writing. Prior to the big move I had spent the last five years at The Denver Post as an editorial assistant and occasional freelance writer. The connection here is a life-long infatuation with the written word. I’ll admit I did what we were all advised not to do on a Library School application: I explained that part of my wanting to become a librarian is because I am in love with books. They accepted me anyway.

From an early age, I’ve digested everything I could get my hands on; books have introduced me to characters that felt like friends; countless hours have been spent with my nose stuck in anything from embarrassingly trashy tabloid magazines to fascinating social justice articles from Mother Jones; and, of course, newspapers have opened my mind to what really matters to me. I like to highlight favorite passages in books and later transfer those passages to a journal. Or, in an act that tells me I’m turning more and more into my mother, I rip out articles from magazines or newspapers and stow them away for future reference. A big part of the connection for me is the tactile experience of handling the medium in which the written word is upon. I love taking an old book off of a shelf and smelling its musty pages; and, although I hated when it got on my clothing, I secretly loved the charcoal stain newsprint left on my hands while working at the Post. All of these experiences led to my involvement with the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) through the Washington State Library.

When I first heard about NDNP, I envisioned an experience in which I could marry my two career interests: journalism  and library science. The obvious draw was the word ‘Newspaper’; the word I was hesitant about, however, was ‘Digital’. Don’t get me wrong, the practicality of digitizing content has not been lost on me, nor has the reasoning behind some news sources going completely digital for that matter; but this doesn’t mean I haven’t been without concern for my beloved “old-fashioned” mediums. However, as a budding librarian in an environment that is experiencing sweeping change, I knew that being a part of NDNP would be an invaluable learning experience for me. I knew there was an entire conversation about digitization that I was missing out on; and here was my chance to be a part of that conversation.

and library science. The obvious draw was the word ‘Newspaper’; the word I was hesitant about, however, was ‘Digital’. Don’t get me wrong, the practicality of digitizing content has not been lost on me, nor has the reasoning behind some news sources going completely digital for that matter; but this doesn’t mean I haven’t been without concern for my beloved “old-fashioned” mediums. However, as a budding librarian in an environment that is experiencing sweeping change, I knew that being a part of NDNP would be an invaluable learning experience for me. I knew there was an entire conversation about digitization that I was missing out on; and here was my chance to be a part of that conversation.

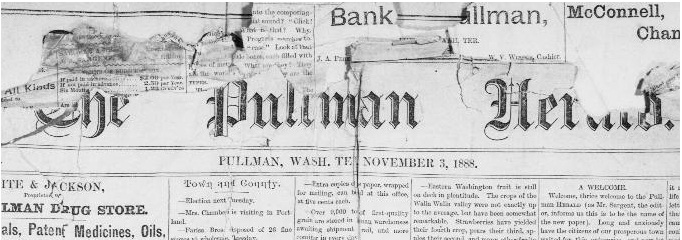

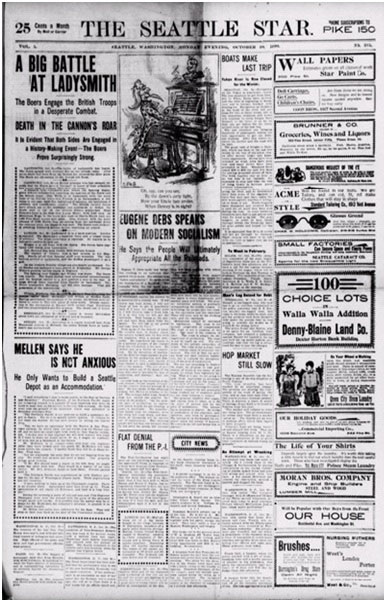

NDNP is a country-wide initiative to digitize historic newspapers between the years 1836 and 1922. The Library of Congress (LOC) and National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) partnered together to make this project possible. Each state chooses one institution to apply for a grant to be a part of the program; after a grant is awarded, this institution can partner up with other institutions in the state to complete the digitization process. Each state is also responsible for selecting its own newspaper titles. In Washington’s case, Washington State Library and University of Washington have taken the reins. Additionally, such agencies as The Association for African American History and Preservation Research, Seattle Public Library, Washington State University History Department, Everett Public Library and Central Washington University have had representatives on the advisory committee for Washington State. Washington became involved with NDNP in 2008 and, as March, 2013, has contributed over 200,000 pages of historic newspapers to the Library of Congress digital repository that houses the newspaper pages: Chronicling America (chroniclingamerica.loc.gov). Currently, 22 states have contributed newspaper pages to the repository. At the fingertips of the public (Chronicling America is an open-access repository – meaning free) is news, as it was unfolding, on the sinking of the Titanic, the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 or – a personal favorite – the first Carnegie Library. Or you can read about historic individuals such as Chief Seattle, Buffalo Bill or the Flapper girls. Stories come alive and context is created from these vessels of information.

And so, every Thursday and Friday morning you can find me in the basement of Suzzallo Library (on UW’s Seattle campus) where I perform a small, albeit important, part of the work-flow process in which newspaper pages are taken from microfilm all the way to what the end user sees on the Chronicling America website. I perform processing tasks on the newspaper pages, such as verifying page numbers (VPN) and optical character recognition (OCR) results. OCR consists of scanning the original newspaper page and converting the text to machine-encoded text, so that original pages can be archived as accurately as possible. The processing tasks must adhere to LOC standards and each state must follow very specific technical guidelines for processing pages. Not all of my work has been technical, however; a large part of my involvement with NDNP has been as an active participant in the access vs. preservation debate, a hot topic in the library field right now.

Do we preserve historic newspaper pages or do we digitize them? Who gets to decide what gets saved in its original form and what is discarded? Are people actually accessing original historic newspapers? These are just some of the questions I asked myself as I entered the preservation vs. access debate. As I first approached the conversation, what I saw was a very black and white issue. I read essays from those that were strictly in favor of preservation, arguing that we have already lost so many valuable historic newspapers therefore making it our duty to preserve those that remain. But then, there is the argument that newspapers take up space and are becoming increasingly inconvenient and expensive to house, making access the most practical solution. One of the reasons this debate is so tricky is that at the heart of the matter is a medium that was never intended for preservation, or access for that matter, in the first place. Publishers in the late 19thand early 20th century certainly didn’t think that librarians in 2013 would be taking efforts to preserve their newspapers; this is evident right down to the medium itself: it tears easily, yellows over time and generally makes for difficulty in preservation.

One of the first questions it is important to pose when discussing this debate is why, with technology available to digitize historical documents, would we want to preserve historic newspapers in the first place? As expressed by my experiences with books, magazines and newspapers, I think there is a certain intrinsic value that can only come from interacting with an original document. An article I read on the subject described it like this: the extrinsic value of a historic document, such as the Declaration of Independence, exists in the information recorded on it; the intrinsic value, however, is the original format independent of the information recorded on it. Imagine if the Declaration of Independence were somehow damaged or destroyed. The impact would be profound and Americans might feel some sort of personal loss with such destruction. Sure, what is recorded on the Declaration of Independence would never be lost –as it can be found in any history book or through a quick Google search – but the value of the original would be gone forever. I believe the same case can be made for historic newspapers; imagine holding the original paper that contained headlines about the sinking of the Titanic. You could run your fingers over the headline and turn the pages in the very spot where someone in 1912 turned the pages. You can see the pictures and details on the page and could be transported to that day in April of 1912. Does a computer screen provide that?

Having worked in print journalism, I witnessed many news sources switching to an online only format; the reality being that it is possible (though it pains me to say) that future generations will grow up in a world where they’ll have no exposure to printed newspapers. These generations need to know about the advent of the printed newspaper and how this medium swept the nation and created context for the way news is reported today. Shouldn’t we preserve historic newspapers for those generations?

Conversely, while those who are pro-access certainly see the value in historic newspapers, they also see the logistical challenges that preserving newspapers creates: whose responsibility is it to decide what gets saved in original form and who pays the rising costs of doing so? Furthermore, as mentioned above, newspapers pose storage challenges for libraries that, more often than not, have budget and space issues to consider.

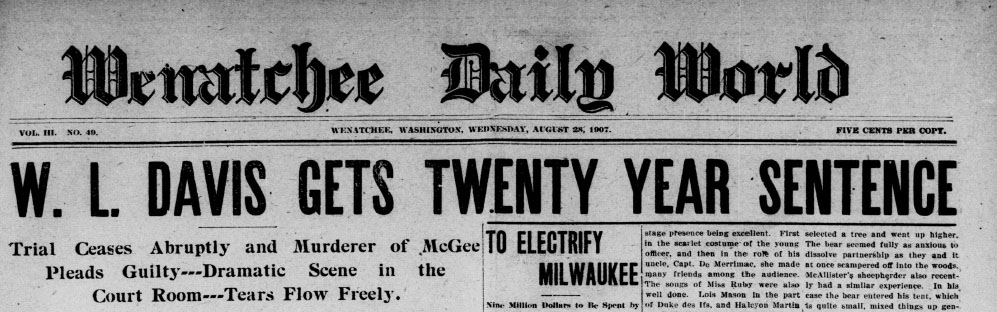

I had the opportunity to talk to Kate Leonard, Conservation Supervisor in the Special Collections department at UW Libraries, about this conversation and she brought up a few points that allowed me to look at the debate from a different angle. Kate and I agree on the tactile experience and how it is such a profound part of interacting with a medium, however, she also pointed out this notion of finding historic documents through access that one would otherwise never find. Because some historic newspapers are rare and housed in research libraries across the country, I might not feasibly access an old copy of The Seattle Times in print were it not for digitization. By providing access, we expose individuals to information they may otherwise not have found or may have never even known was out there in the first place. This aspect of the debate has personally affected me; as I perform my work with NDNP, making OCR corrections here and there on old issues of the 1908 edition of The Seattle Times, I’ve happened across articles about my new surroundings that have provided me with a rich layout of Washington State’s colorful history. I now know about Washington’s road to Statehood in 1889 or the Walla Walla Massacre of 1847 that later led to the Cayuse War between the Cayuse people and local Euro-American settlers. In fact, just the other day my colleague and I were saying that some articles we happen across make us feel like we aren’t so different than the men and women of the early 1900’s. There was an article about Seattle’s terrible traffic, written in The Seattle Time’s 1908 paper, and the last time I checked the traffic in Seattle was still terrible and a topic of constant conversation among residents. Or there are the same sensationalist stories that the media decides is newsworthy enough to devote their attention to over other – often similar – stories; such as the Davis barroom murder trial of 1907, covered extensively in the Wenatchee Daily World.

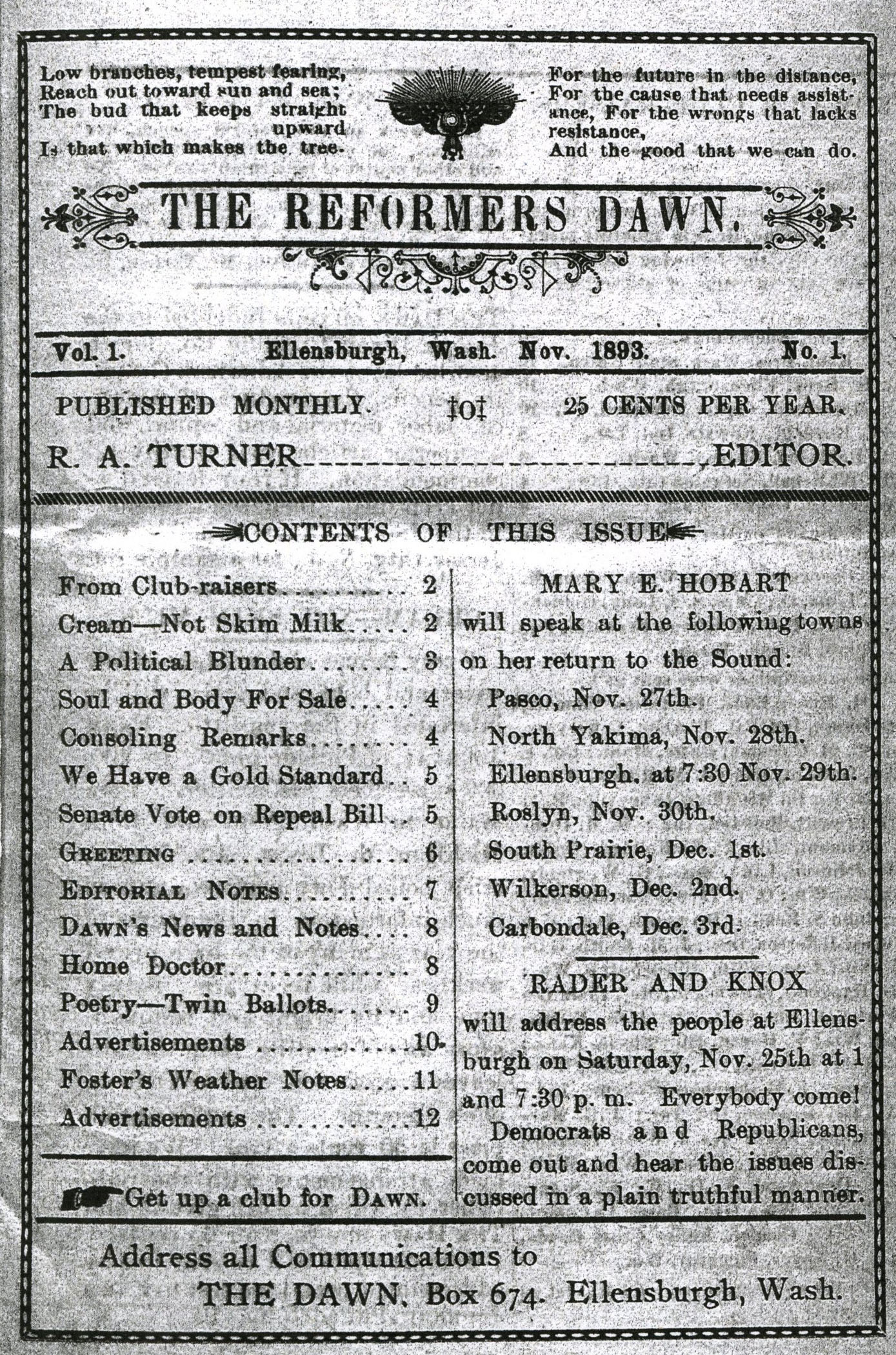

Kate also brought to my attention an issue that came up recently in which The Reformer Dawn – the earliest known publication of what eventually became the Ellensburg Dawn, running from November 1893 to January 1894 – posed serious digitization issues. The paper is the size of a pamphlet and has been bound and stitched at the binding to prevent further damage to its already fragile pages and spine. The desire to digitize this paper proved to be dicey, as it would have required unstitching the binding to scan the pages. Thankfully those measures were not taken and Kate and her Special Collections team were able to take digital photos of the paper, which were later uploaded as TIFF files and added to the Chronicling America repository. The Reformer Dawn will also remain as a part of WSL’s permanent digital collection. Because The Reformer Dawn is in danger of being housed in “dark archives” (a dungeon-like place where historic documents go to spend the end of their lives) this is yet another example of access providing individuals a chance to interact with documents they may otherwise never have had the opportunity to do so with.

Kate also brought to my attention an issue that came up recently in which The Reformer Dawn – the earliest known publication of what eventually became the Ellensburg Dawn, running from November 1893 to January 1894 – posed serious digitization issues. The paper is the size of a pamphlet and has been bound and stitched at the binding to prevent further damage to its already fragile pages and spine. The desire to digitize this paper proved to be dicey, as it would have required unstitching the binding to scan the pages. Thankfully those measures were not taken and Kate and her Special Collections team were able to take digital photos of the paper, which were later uploaded as TIFF files and added to the Chronicling America repository. The Reformer Dawn will also remain as a part of WSL’s permanent digital collection. Because The Reformer Dawn is in danger of being housed in “dark archives” (a dungeon-like place where historic documents go to spend the end of their lives) this is yet another example of access providing individuals a chance to interact with documents they may otherwise never have had the opportunity to do so with.

Given the evidence of both preservation and access providing rich educational experiences for all users, I began to wonder why some present the debate as so black and white. The way I see it, there is so much gray area; a gray area in which we can provide both preservation and access. Some librarians and archivists suggest a model in which responsibility for both original and surrogate documents is distributed among institutions. And isn’t this the very purpose of a library in the first place: to preserve documents that provide the public with lasting value so that future generations can access them, be it in its original or surrogate form?

All of this leads to an increasingly important question: if we know now how much we drastically want to save historic newspapers of the past, what steps are we taking to preserve digital information of the present? After all, building and maintaining a digital repository is a completely different ballgame than preserving old newspaper pages. Each medium has its own benefits and downfalls as it pertains to preservation techniques but, as opposed to newspaper print, building a digital repository is an area of preservation that archivists are still exploring and fine-tuning best practices. Similarly, a digital repository is much different to maintain because digital objects will always need a software environment to render it; newspapers, however, provide unmediated access to content. Important to consider is the way computer systems age much faster than data media; something new is always in the works and we are constantly upgrading.

Today, archivists are implementing a slew of preservation techniques for digital content. In the case of Washington’s involvement with NDNP, we are involved in a work-flow process that takes microfilm to transferable TIFF files and on through a series of processing tasks and quality control checks before we finally send the files, along with the microfilm, to Library of Congress. LOC then uploads these files and now users can access the newspaper pages on Chronicling America. During the processing and quality control checks, we are performing tasks such as text correction, cropping and de-skewing pages and other various measures that will enable the end user to more accurately access pages and read articles. Furthermore, Washington State Library will maintain all of the files we create in their digital collection; making Washington State residents aware of this expanding digital collection is yet another step the library is taking towards providing access.

While I’d certainly never call myself a Luddite, it was a rather big leap to immerse myself in the digitization world. When I approached the project, I wondered if digitizing documents would make originals, at least over time, obsolete; as it turns out, librarians don’t want that at all. They simply want to make access just as important as preservation; they want to provide entry to the all-important grey area: an area where users find both preservation and access. And though I’ll take sipping coffee and dropping muffin crumbs over a daily print newspaper, the efforts LOC and NEH are taking to make historic newspapers available is nothing short of amazing. It is our duty as information professionals to provide access to documents that are rich in value and history, such as newspapers. Just as we take effort today to save papers from the past, so too are we taking efforts to preserve the news we see today on our computer screen, for tomorrow.