Unity Through Disaster: Yakima’s Cleanup after the Eruption of Mount St. Helens

May 18, 1980, a day many Pacific Northwesterners vividly remember, was the infamous day Mount St. Helens erupted and left much of the state in complete darkness. This day was coined “Black Sunday,” and during the following week, nearly 200,000,000 cubic yards of soot and ash were dumped across Washington and covered nearly half the state.[1]

The City of Yakima was in the direct path of the ash plume. To make matters worse, the volcano would continue to emit ash for the next eight days, which halted the normal processes of the city. In a letter to President Jimmy Carter that outlined the extent of the city’s cleanup efforts, Betty L. Edmondson, mayor of Yakima at the time, stated all the city’s resources were committed to return the city to functional levels.[2]

However, this was not enough. The city had to ask for outside assistance from the City of Seattle, King County, the City of Portland, various counties across Oregon, and private entities. Even with all this assistance, Mayor Edmondson wrote, “the magnitude of coping with the ash fall-out far exceeds present manpower and equipment resources on hand.” With no immediate help from federal or state government, Yakima was left to their own devices to clean up their city.

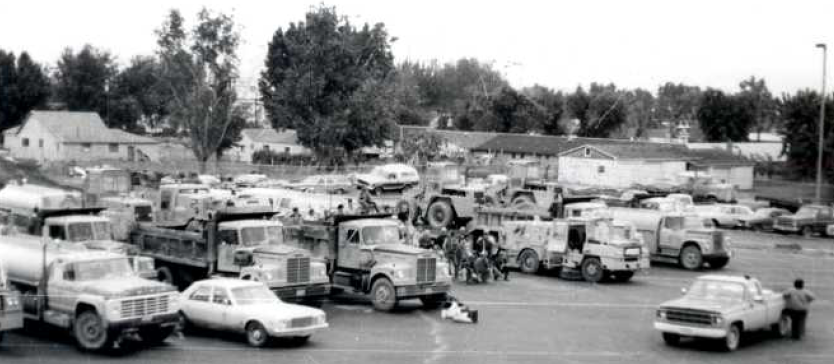

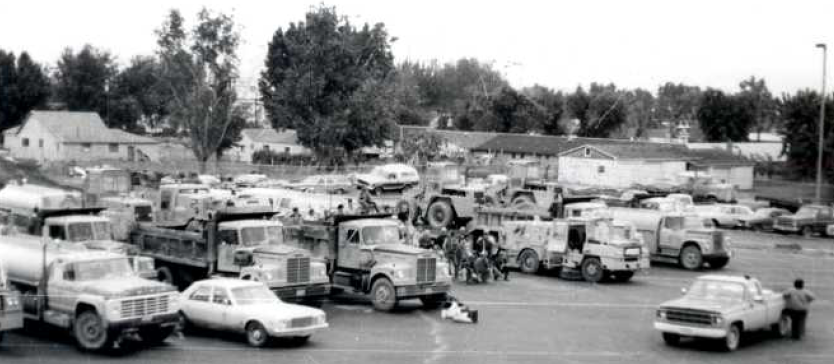

Natural disasters, as devastating as they are, have the miraculous power to unite communities. The newspapers of Yakima made sure to record the actions of the city’s citizens and community groups. An article titled “Community pulls together to get rid of the grit,” published by the Yakima Valley Sun on May 29, 1980, outlined the unity in the city.[3]

The article especially emphasized the unity between citizens and their city government officials. It reported, “Private citizens and government employees alike donned jeans and a wide variety of dust muffles, then pitched in to clean up. People who spend their usual work days [sic] doing advanced planning for the city were pushing brooms at the airport and in municipal parking lots.” With the city currently at a standstill, everyone had to pitch in to make the city come back to life.

A separate article published by the Yakima Herald-Republic, titled “City asks resident cleaners to be patient,” on May 29, 1980, showed the determination of Yakima’s citizens in taking control of the ash disaster.[4]

The article states nearly 150 neighborhoods had fully cleaned the ash from their roads and houses, all within four short days after the last major ashfall.

Well over a year after the eruption of the volcano, Mayor Edmondson presented the impact of the multiple eruptions on Yakima’s city government at the national Volcanic Hazards Workshop in Sacramento, California.[5]

In this presentation, the mayor stated the city had expended nearly $2 million to clean the massive amount of ash from the city. Among other data and statistics, the mayor herself made sure to emphasize the power of the community during natural disasters. She mentioned service clubs, granges, churches, and even private citizens were more than willing to come together to bring their town back to a functional level.

Edmondson also talked about an unlikely but beneficial resource during citywide emergencies. She said, “The Director of the library proved to be a great source of information – using the resources of the library in an emergency situation is a must!” She never went into detail about the library’s contribution. However, it goes to show knowledge and the work of those tasked to preserve knowledge will always be a positive resource within communities.

This collection features a plethora of newspapers, geological surveys, photographs, bulletins, and many more insightful and interesting documents, all of which are readily available for viewing at the Washington State Archives Central Region Branch in Ellensburg.

What might you uncover from these fascinating documents?

-Jordan Hughes, Central Branch Intern

Notes

[1] Betty L Edmondson, “Impact of the Eruptions on City Government,” (1981), 5.

[2] Betty L Edmondson, letter to President Jimmy Carter declaring a state of emergency in the city of Yakima, (1980).

[3] Patricia Brown, “Community Pulls Together to get rid of the Grit,” Yakima Valley Sun, May 29, 1980, 1.

[4] Kate Myra, “City asks Resident Cleaners to be Patient,” Yakima Herald-Republic, May 18, 1980, 1.

[5] Edmonson, “Impact of the Eruptions on City Government,” 4.

2 thoughts on “Unity Through Disaster: Yakima’s Cleanup after the Eruption of Mount St. Helens”

Nice article, Jordan! Will look forward to seeing more of what you uncover!

What a great example of community coming together. Thank you for researching and sharing this bit of history.

Comments are closed.