From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

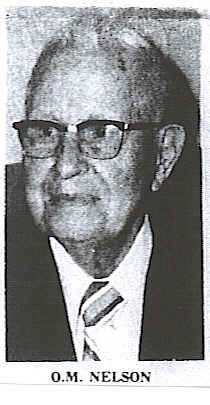

Several years ago I discovered an unusual Washington State connection to Earth Day while compiling biographical information about unsuccessful candidates for Governor. The election was 1936 and the subject was Union Party nominee Ove Malling Nelson.

Although a bit distant, the connection is this: Ove Nelson was the uncle of the Sen. Gaylord Nelson, the Father of Earth Day. OK, so its convoluted, but I love trivia.

Although a bit distant, the connection is this: Ove Nelson was the uncle of the Sen. Gaylord Nelson, the Father of Earth Day. OK, so its convoluted, but I love trivia.

Attorney and author O.M. “Ovie” or “Ovey” Nelson was a political gadfly and fixture in Grays Harbor County elections for thirty years, 1916-1946. Most of his energy was spent running for either County Prosecuting Attorney or the 3rd District U.S. Congress seat. One reference mentioned he also tried for the State Senate at some time. He ran under the banner of four different parties in the course of his campaign career: Republican, Democrat, La Follette Progressive, and Union. This last party was the strangest of them all, and he was identified with it during a curious detour from his pattern of trying to obtain the above mentioned offices. Nelson was the Union Party’s candidate for Governor in 1936.

Ove Malling Nelson was born Mar. 9, 1880 in Thorp, Clark County, Wis. His parents were immigrants from Norway. He came from a large farming family where politics was apparently in the genetic fiber.

In a May 27, 1999 “countdown to the millennium” piece, the Montesano Vidette included this background on Nelson:

Raised in the mighty Wisconsin forest, his father carved a log home from the forest and would travel 40 miles for food, which he packed on his back. Young Ovey also attended school in a log school house in Thorp, receiving his diploma when he was 14 years old.

“Dissatisfied with the next three years of his life working on a farm, Ovey decided to take a high school course. He had to walk four miles to attend class and once there he was the only boy in a class of four students. Ovey then turned to teaching, but dissatisfied with the Wisconsin frontier, he decided to travel west, arriving in Everett in 1900.

Young Nelson stayed in Washington until 1906, when he decided to move back to Wisconsin. There he worked as a stenographer and bookkeeper. It was also during this time he met the future Mrs. Nelson, Melinda Opperman. The couple later married in Seattle in 1915 and they had three sons.

Nelson’s stay in Wisconsin only lasted a short time though. He moved back to Seattle in 1907 and it was two newspaper advertisements that played an important part in his life.

The first ad he answered was for a company seeking a man to work out of town. Thus he came to Cosmopolis in January 1907 with C.F. White to work for Neil Cooney and the Grays Harbor Commercial Co.

Nelson worked for Cooney for eight months when he answered a second ad by W.H. Abel of Montesano for a stenographer. Nelson was hired. During this time, Nelson became interested in the law. He found time to read law in the evenings.

Nelson worked for Cooney for eight months when he answered a second ad by W.H. Abel of Montesano for a stenographer. Nelson was hired. During this time, Nelson became interested in the law. He found time to read law in the evenings.

Nelson worked for Abel for one year, one month and 16 days, before heading to Olympia to take the bar examination, which he passed. In 1909 he set up an independent practice for himself.

Somewhere in that narrative, according to his obituary, Nelson attended business college in Oshkosh, Wis., probably in 1906.

Nelson’s political runs appeared to have started in 1916. Between 1916-1946 he ran for County Prosecuting Attorney at least four times, and made no less than eight attempts for U.S. Congress. Apparently he sat out the elections of 1932, 1940, and 1944. In the other years I have identified 13 attempts by Nelson to gain elective office. In eight of those he ran as a Republican but never gained enough votes to win a primary. The only way he was able to get his name on the general election ballot was to run as Democrat, Progressive, or Union party member. In most of these elections, he usually won the majority of votes in his home town, which says a lot about his standing in the community and the perseverance of Monte in supporting their own favorite son against the much more populated Aberdeen-Hoquiam or Olympia political base.

In 1922 Nelson made his first bid for U.S. Congress. Nelson’s Big Issue in the 1920s appears to be that he was a “wet,” arguing that Prohibition was a mistake.

In 1924 Nelson ran for Congress as a member of La Follete’s Progressive Party. The Democrats apparently didn’t have a real candidate so Ovie became the main opposition by default. Nelson pretty much mouthed the party line on national issues. In local affairs, he promoted the idea of public ownership of utilities. The Grays Harbor Public Utility District was still 14 years away. Ovie was ahead of his time on this issue.

Prohibition was a major story issue in the region. The Grays Harbor County Sheriff and a host of other law enforcement types had been stung in booze running conspiracies. Alcohol was brought down from British Columbia, dumped overboard in crates into Grays Harbor, where local distributors picked them up under the watchful and approving eye of the local law. Meanwhile, out in McCleary, a thriving cottage industry of producing quality homemade booze helped supplement the local economy. “McCleary Moonshine” even had a special label.

In 1930 he tried again to unseat incumbent Albert Johnson in the primary. According to the Montesano Vidette, Sept. 4, 1930:

NELSON WANTS NEW DRY LAW

O.M. Nelson, Montesano attorney, is waging a vigorous campaign for representative in congress. He will speak over KMO, Tacoma, Thursday night and Saturday night. His campaign is based chiefly on his proposal to rectify prohibition condition by adoption of another amendment to permit government sale of liquor under proper regulation. He would leave the present amendment intact to prevent the return of the saloon. He has cited the Lyle-Whitney case in Seattle as an example of what he terms the failure of the national prohibition law. He lays the crime wave and much of business depression to prohibition. Nelson is city attorney of Montesano, having been reelected several times.

And although he placed first in Montesano, he finished 3rd in the primary in 1930. Interesting to note his position as City Attorney was an elective office, so he was successful in municipal elections.

The repeal of Prohibition had taken away the topic that had been Ovie’s main campaign issue for years. It was replaced by his interest in monetary reform. In 1934 he authored On the Wane: Democracy Or Communism (Montesano Publishing Co.), a 192 page book the Montesano Vidette said “attacks our banking system and which declares our present money system, based on huge debts, is destroying democracy and opening the door to communism.” Copies of this monograph are difficult to find today.

Now for a little background on the Union Party. It was a brief blip on the political radar, initially causing panic among Democrats but as it turned out was of little consequence in the election. The Party’s foundation was built from three groups who felt FDR was not doing enough to meet the financial crisis of the 1930s: The Townsendites, the Coughlin listeners, and the Share Our Wealth followers.

The historian William Manchester gives his take on the Union Party: “… Father Coughlin and his colleagues preempted the lunatic fringe, presenting for the voters’ consideration their new Union Party. The Union candidate for President was Congressman William Lemke of North Dakota, a strange individual with a pocked face, a glass eye, and a shrill voice; to the radio priest’s dismay he insisted upon wearing a gray cloth cap and an outsize suit. Coughlin baptized him ‘Liberty Bill,’ and Gerald L.K. Smith drew up plans to guard the November polls with a hundred thousand Townsendite youths. The radio priest promised to quit the air forever if he didn’t deliver nine million votes for the Union ticket. That seemed extravagant, but in June both major parties were taking Lemke seriously … The sobriquet ‘Liberty Bill’ was catching on. Father Coughlin rather liked the alliterative resemblance to ‘Liberty Bell.’ Then, too late, he remembered something: the Liberty Bell was cracked.”

The Washington State Union Party met at the Frye Hotel in Seattle and nominated Nelson for Governor. National organizer H.F. Swett predicted to the Seattle Daily Times the Union Party “would carry Wyoming and Idaho and that the ticket would make a creditable showing in Washington.”

Nelson clearly saw himself as coming from the Left in his Union Party run. Incumbent Gov. Martin was a moderate Democrat. The Washington Commonwealth Federation, a liberal political action group which included Townsendites in their ranks, had failed to displace Martin in the primary. Part of this was due to the fact 1936 was the first blanket primary in Washington, and many Republicans crossed over to choose the least objectionable Democrat. Meanwhile, former Governor and extreme conservative Roland Hartley, who was defeated in 1932 by Martin, won the Republican primary. Nelson tried to capitalize on the fact the Left had nowhere to go. Here’s part of an article from the Sept. 17, 1936 Montesano Vidette:

NELSON SAYS LIBERALS TO ELECT HIM GOVERNOR. MONEY IS THE ISSUE, SAYS CANDIDATE

Following the lead of the union party’s presidential candidate, William Lempke, who insists he will be elected president in November, O.M. Nelson, Montesano’s first gubernatorial candidate, declares he will be the next governor of Washington …

Despite the fact that his is frankly a minority group, Nelson forsees a coalition of liberal political voters in the state who won’t vote for ‘those two reactionaries, Martin and Hartley.’ This coalition will vote for the union party candidates, Nelson declares.

“Money is the issue,” Nelson says. “All other issues are subordinate to the issue of honest money. Most of our economic problems are the direct result of our present dishonest money system. As soon as people wake up, they will realize they have been robbed for years and will put an end to dishonest money.”

Martin, meanwhile, was no slouch when it came to political fence mending. Two other third party gubernatorial challenges, both of them with Townsendites in their ranks, were quelled before they had chance to file for the ballot.

Nelson did campaign throughout the state. He is on record as speaking to large groups in Walla Walla, Colfax, Spokane, Ellensburg, Davenport, Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia.

It didn’t do any good. Gov. Martin was re-elected with almost 70% of the vote. Nelson placed third out of the eight candidates with 6,349 votes (0.94%). He seemed to have a bump in votes in Clallam, Clark, Grays Harbor, Lewis, Mason, Pierce, Thurston, Walla Walla and Yakima counties, but even then he was never close to finishing at second place. The six third party candidates combined total only accounted for 2.52% of the vote.

Nationally and locally the Democrats enjoyed a huge landslide. The Republicans would be down to 5 senators and 6 representatives in the 145-member Washington State Legislature in the 1937 Session. The Argus ran this bit: “The day after election four years ago Jay Thomas, who was then public printer, stepped down to the lobby of the Olympian Hotel and let out a yell, ‘Look at me, the last living Republican.’ Recalling this incident, an old timer remarked here this morning after this election, ‘and now Jay is dead.'”

The Union Party evaporated after the 1936 election, but Nelson didn’t give up trying to get elected to public office. He made at least three more attempts to win the Republican primary for U.S. Congress. As usual, if it had been up to Montesano voters alone he would’ve been elected, but he couldn’t get the district-wide support.

In 1946 he ran one last time for Congress as a Republican under the catchy slogan: “We can produce abundance every day and we should be able to live abundantly every day without ruining the nation and ourselves with debts.” Although he seldom ran political newspaper ads in his early years, he came around at the end.

Ovie apparently retired from his quest for public elected office after 1946, but he remained very active in civic affairs. In the post-War years, he donated a chunk of land to Montesano for use as “Nelson Field,” a Little League Baseball park. In 1960, at the age of 80, he wrote his best known work: Our Legalized Monetary Swindles (New York : Vantage Press).

Ovie was still an active and a sought after speaker into his 90s. He died suddenly during the Grays Harbor Bar Association Christmas party at the Nordic Inn in Aberdeen, Dec. 19, 1975. His front page obituary stated, “At the time of his death he is believed to have been the oldest practicing attorney in the state.”

John C. Hughes, the Chief Historian of our own Legacy Project here at the Office of Secretary of State, shares this memory of Ove Nelson:

When I covered the Courthouse for The Aberdeen Daily World in the late 1960s, I visited O.M. Nelson several times at his office in Montesano. It was like having an audience with Teddy Roosevelt, William Jennings Bryan or H.L. Mencken. Today we seem to have few genuine, iconoclastic, larger than life characters who aren’t dogmatic windbags. Nelson was all over the political map during his long career, but never motivated by opportunism. He waved his arms passionately when he warmed to a subject. Considering that all around him—on the desk, the floor and bookcases—papers were stacked two or more feet high, some leaning precariously like the tower at Pisa, I always worried that one false move could trigger a catastrophe. Nelson claimed he could quickly locate anything he needed in all the clutter. I never tested him. His grandson, Greg Nelson, Aberdeen’s city attorney, says grandpa’s secretary once heard a loud thump inside his office and feared he had fallen. It was just a mound collapsing onto the floor.

My, my, this post sure strayed a bit from Earth Day. Such is the interdisciplinary nature of history.

![Dia2013_12x18Poster_download_0[1]](https://blogs.sos.wa.gov/library/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Dia2013_12x18Poster_download_01-255x300.jpg) April 30 marks Día, the culmination of El día de los niños/El día de los libros (Children’s Day/Book Day).

April 30 marks Día, the culmination of El día de los niños/El día de los libros (Children’s Day/Book Day). Storm Boy. By Paul Owen Lewis

Storm Boy. By Paul Owen Lewis The Great Migration. By Jacob Lawrence

The Great Migration. By Jacob Lawrence The circle of equilibrium: poems of conscience and leadership by Native, Latino, African and Asian American youth

The circle of equilibrium: poems of conscience and leadership by Native, Latino, African and Asian American youth Color: Latino voices in the Pacific Northwest

Color: Latino voices in the Pacific Northwest I am Sacajawea, I am York: Our Journey with Lewis and Clark. By Claire Rudolf Murphy.

I am Sacajawea, I am York: Our Journey with Lewis and Clark. By Claire Rudolf Murphy. Seeking light in each dark room: those who make a way, young Latino writers in Yakima = Buscando luz en cada cuarto oscuro: por los abrecaminos

Seeking light in each dark room: those who make a way, young Latino writers in Yakima = Buscando luz en cada cuarto oscuro: por los abrecaminos Nosotros: the Hispanic people of Oregon : essays and recollections

Nosotros: the Hispanic people of Oregon : essays and recollections