From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

The irony of hermits is that the more they desire to be alone, the more attention they garner. The hermit becomes an object of curiosity. For example, a character by the name of “Buckskin Joe” certainly got my interest when I randomly found the following short article on the front page of The Concrete Herald, Feb. 21, 1914:

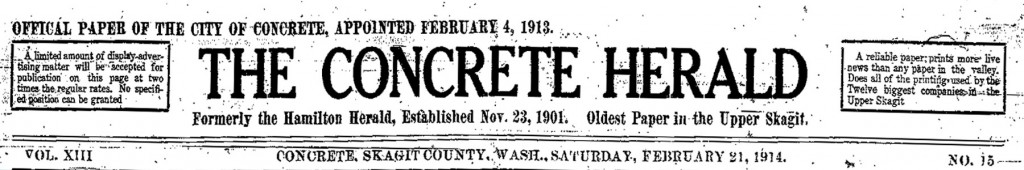

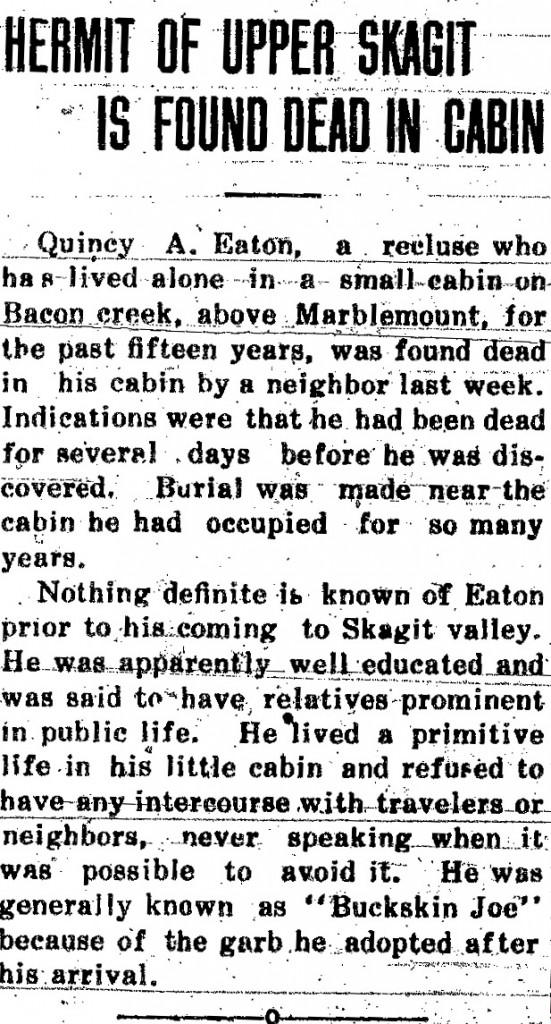

HERMIT OF UPPER SKAGIT IS FOUND DEAD IN CABIN

“Quincy A. Eaton, a recluse who has lived alone in a small cabin on Bacon creek, above Marblemount, for the past fifteen years, was found dead in his cabin by a neighbor last week. Indications were that he had been dead for several days before he was discovered. Burial was made near the cabin he had occupied for so many years.”

“Nothing definite is known of Eaton prior to his coming to Skagit valley. He was apparently well educated and was said to have relatives prominent in public life. He lived a primitive life in his little cabin and refused to have any intercourse with travelers or neighbors, never speaking when it was possible to avoid it. He was generally known as ‘Buckskin Joe’ because of the garb he adopted after his arrival.”

Thanks to the Chronicling America project, I was able to locate one article about Buckskin Joe during his lifetime. It came from the June 30, 1897 issue of the San Francisco Call. It was headlined: WILD MAN OF SKAGIT COUNTY.

Identified simply as Buckskin Joe, farmers and miners in the area testified in the article that this wild hermit had set up a couple primitive structures on Bacon Creek. One of them was a strange convoluted tree house, from which Joe watched any visitor. “He absolutely refuses to associate with any one and always carries a rifle, a revolver, and a big knife. His cartridge belt holds an immense amount of ammunition and is always around his neck. He is nearly asleep until some one comes within hearing distance, when his frightful-looking head appears and the visitor looks into the barrel of his rifle.”

The nearest big city newspaper to cover Joe’s demise was the Bellingham Herald. The headline read HERMIT LEAVES NO TRACE OF IDENTITY IN DEATH in the Feb. 18, 1914 issue.

This article included: “For nine years the government has permitted him to live within the forest under sufferance. He had been dead in his bed for probably two weeks when his cabin was entered last week. A traveler’s dog howling at the door of the cabin attracted attention to the place and a resident investigated when he received no response to his calls for the hermit. The body was interred in the rear yard of the cabin, under the potato patch which the hermit cared for studiously during past years.”

“Despite several attempts to make him sociable, the hermit remained ‘the silent man of the mountain.’ He would pass wayfarers with his head down, refusing to acknowledge salutation or greeting. Where he came from or what his connections were is not known further than at one time he tersely informed residents that his brother was a United States senator.”

Except for a brief mention in JoAnn Roe’s 1997 book North Cascades Highway : Washington’s Popular and Scenic Pass, a superficial survey of Skagit County historical material didn’t turn up any information on Buckskin Joe.

However, there is one document that serves as a stepping stone in uncovering Buckskin Joe’s past: The U.S. Census. He is in there for 1910. It is so strange a hermit like Buckskin Joe would be so cooperative in providing information, but perhaps the Feds told him that if he wanted them to continue turning a blind eye to his presence on public property, he better play along.

With the help of our online genealogical resources at WSL I was able to locate more documents and eventually came into contact with Cheryl Eaton, one of the historians for that family. She was able to fill in several gaps.

Quincy Adams Eaton was born Oct. 5, 1849 in Lanawee County, Mich. He was the 7th of the 11 children of Christopher Columbus Eaton (1810-1877) and Eleanor (Lamberson) Eaton (1817-1893). Quincy was apparently known as “Tuney.”

According to Cheryl, Christopher Columbus Eaton “was a forward thinking man and most of his children graduated from the State Normal School in Ypsilanti, MI or the Michigan Agricultural College.” By the early 1870s, many members of the Eaton family had migrated to Colorado Territory to join the Union Colony at Greeley.

For some reason Quincy’s application for a deed at Union Colony was refused, Mar. 21, 1871. He migrated to the area of present-day Merino, Colo., where he taught school, ran a stagecoach line and mail route (soon made obsolete when the railroad arrived), and possibly raised cattle. He apparently never married. After 1882 he vanishes from the record until he shows up as “Buckskin Joe” in Skagit County, Wash. over a dozen years later.

For some reason Quincy’s application for a deed at Union Colony was refused, Mar. 21, 1871. He migrated to the area of present-day Merino, Colo., where he taught school, ran a stagecoach line and mail route (soon made obsolete when the railroad arrived), and possibly raised cattle. He apparently never married. After 1882 he vanishes from the record until he shows up as “Buckskin Joe” in Skagit County, Wash. over a dozen years later.

By the time he was discovered up here, most of his family had passed on. One brother had been killed in the Civil War, and another, George Washington Eaton, was killed by Ute Indians in the Meeker Massacre, Sept. 1879. Although Quincy was not related to any U.S. Senators, his brother Oscar Eaton (1847-1895) was a banker and prominent Ohio Republican, having attended the 1892 National Convention as a delegate.

So where was Buckskin Joe 1882-1896? What drove him into the woods to lead a life of militant solitude? If you have any additional information on this intriguing character in Washington State history, we would love to hear from you.