From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

I stumbled across a legal case in Washington State history that deserves to be revisited. The following news nugget was found at random in the Morning Olympian for May 5, 1916:

DEFAMER OF GEORGE WASHINGTON GUILTY

JURY RETURNS WITH VERDICT AFTER 90 MINUTES

“TACOMA, May 4.–Paul R. Haffer was found guilty of libel and defamation of character when he said that George Washington drank more liquor than was good for him and used occasional profanity. A jury in the superior court so decided last night after deliberating an hour and 30 minutes.”

“Col. A.E. Joab brought the charge against Haffer after the latter had written a letter to a newspaper on Washington’s birthday, setting forth the alleged delinquencies of the father of his country. In his own defense, Haffer said that he had read much of Washington’s life, and wrote the charges because he was opposed to hero worship, and he thought the people were making too much of Washington’s memory. He is a socialist and employed as a car repairer. The maximum penalty for the offense is a year in jail and $1,000 fine. An appeal will be taken.”

“Col. Joab thanked each juror as they filed from the box for being ‘a real American.'”

OK, probably not a good idea to be an iconoclast in a state named after George at a time when America was nervous about socialists and the possibility of entering the Great War, which was already underway in Europe. Also, Prohibition was the law of the land in Washington State by 1916, and comments about drunkenness were not taken lightly. But the Haffer case was not one of the most shining moments in the legal history of The Evergreen State.

Haffer was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan ca. 1895. His family moved to the Tacoma area when he was about 9. He was apparently a strong socialist throughout his entire life.

The exact content of his letter to the editor of the Tacoma Tribune for the issue in question remains murky. It was  published on Feb. 18, 1916, but that issue is mysteriously missing from our microfilm reel for that time slot, even though every issue around that date is intact. If anyone out there has the full contents of Mr. Haffer’s letter, I’d appreciate seeing it.

published on Feb. 18, 1916, but that issue is mysteriously missing from our microfilm reel for that time slot, even though every issue around that date is intact. If anyone out there has the full contents of Mr. Haffer’s letter, I’d appreciate seeing it.

However, other newspapers quoted parts of it. The Tacoma Times: Haffer said Washington was a “slaveholder, a profane and blasphemous man and an inveterate drinker.” The first accusation was certainly true, but the next three are very open to debate and definition.

Haffer’s reply to the press was that he wrote the letter “to check the unthinking idolatry of heroes held up by demigods before the public.”

The day following publication of his letter to the editor, he was charged with criminal libel by Col. Albert E. Joab (1857-1930), a self-appointed guardian of “patriotic values” and considered as something of a “picturesque” character by the local press. It is interesting Col. Joab went after the writer rather than the newspaper that published the piece.

The Tacoma Tribune had no comment on the case, but the rival Tacoma Times exalted in it. They quoted Col. Joab as calling Haffer a “Damnable blackguard, infamous anarchist, Red socialist!” Also these choice quotes: “I’ve been raised all my life to respect men such as Washington and I don’t propose to stand for a red anarchist to desecrate his memory. Thank God I’ve got some red blood in my system to stick up for Washington, if nobody else will. I don’t know who the man is who wrote the article, but he undoubtedly is a socialist. You can tell a rabbit by his track. He is a —- blackguard. Let this man prove in open court what he says of Washington, if he can. I can produce articles by Thomas Jefferson, whom we all learned to love through Woodrow Wilson, Ben Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and others, showing Washington was an upright man, noted for his sobriety. Why, he was even a communicant of the Episcopal church and a Master Mason. Look in any standard dictionary and you will see Washington’s picture in his Masonic apron.”

Haffer was convicted in Pierce County Superior Court and the decision was upheld, incredibly, after an appeal to the Washington State Supreme Court. Haffer was fined and sentenced to several months imprisonment, but after a month of serving his time he was pardoned by Gov. Lister.

But Haffer and the legal system still had another issue to sort out. Like many other socialists, Paul was opposed to the U.S. entry into the Great War in 1917, and according to Albert F. Gunns in Civil Liberties in Crisis : the Pacific Northwest 1917-1940 Haffer was forced into the Army after serving 10 months in jail for refusing to register for the draft. He served his time in uniform at Camp Lewis and was honorably discharged in 1919 having never been overseas.

In spite of all the contemporary publicity over his radical views, Haffer might be better remembered today as the one-time husband of the innovative and acclaimed photographer Virna Haffer (1899-1974). Paul and Virna had a son, Jean Paul, in 1924 before they divorced a few years later.

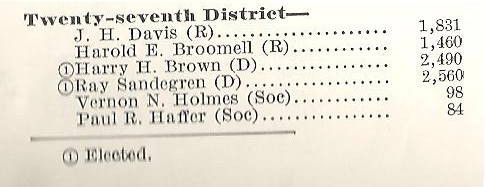

In the 1930s and 1940s Haffer remarried, started a second family, had another son and obtained work as a shipfitter. He ran for State Representative in 1934 as a member of the Socialist Party and placed 6 out of 6 in the primary with 0.99% of the vote. None of the slings and arrows hurled at him in earlier years had distracted him from his original vision.

When Haffer died on June 15, 1949 at age 54, his obituary mentioned he “gained brief notoriety when he was convicted in a Tacoma court of libeling George Washington on charges brought by the late Col. Albert Joab.”