From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library

It was a criminal story bound to generate headlines. Federal agents storm a mansion in Seattle, the home of a former Governor’s son. In the course of their search they discover a large amount of a white powdery substance hidden behind a sofa and an arrest is made.

It was flour. Around 600 pounds of it.

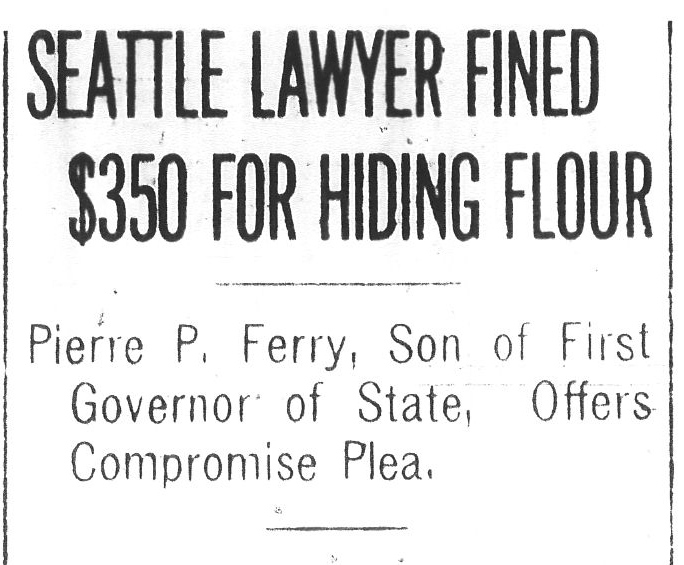

Here’s the report from the Seattle Daily Times, August 2, 1918:

SEATTLE LAWYER FINED $350 FOR HIDING FLOUR

Pierre P. Ferry, Son of First Governor of State, Offers Compromise Plea.

“Charged with hoarding flour in violation of the food laws, Pierre P. Ferry, wealthy pioneer attorney and son of Elisha P. Ferry, first governor of the state, last night was fined $350 by Judge Edward E. Cushman in the United States District Court. Ferry paid the fine and costs at once.”

“Ferry was the first man to be arrested in Seattle on a charge of food hoarding. He was taken in custody early last month when federal officers found more than 600 pounds of flour behind a sofa in the maid’s room on the third floor of the Ferry residence, and subsequently he was indicted by the grand jury.”

Offers Compromise Plea.

“Arraigned last night, Ferry was permitted by the court to enter a plea of nolle contendere. This is a compromise plea involving neither the guilt nor innocence of the defendant. Speaking for the government Assistant United States Attorney Ben L. Moore declared Ferry should plead either guilty or not guilty.”

“Moore also declined to suggest the amount in which Ferry should be fined or otherwise punished. The government prosecutor merely placed the facts in the case before the court, declining to be heard further than a statement that Ferry either was guilty or not guilty and should be compelled so to plead.”

Denies Attempt to Conceal.

“Former Federal Judge C.H. Hanford, who, with Alfred Battle and J.L. Corrigan, represented Ferry, contended that the defendant had not been guilty of an attempt to violate the spirit and intent of the law and had made no effort to conceal the flour. He said Ferry did not know he held an unlawful amount of flour until so notified by federal agents.”

“Judge Cushman said that while he did not countenance food hoarding, if the country was at a point where it was starving such an offense would call for harsh punishment and the rule of guilt or innocence demanded. He said he was thankful that time is not here.”

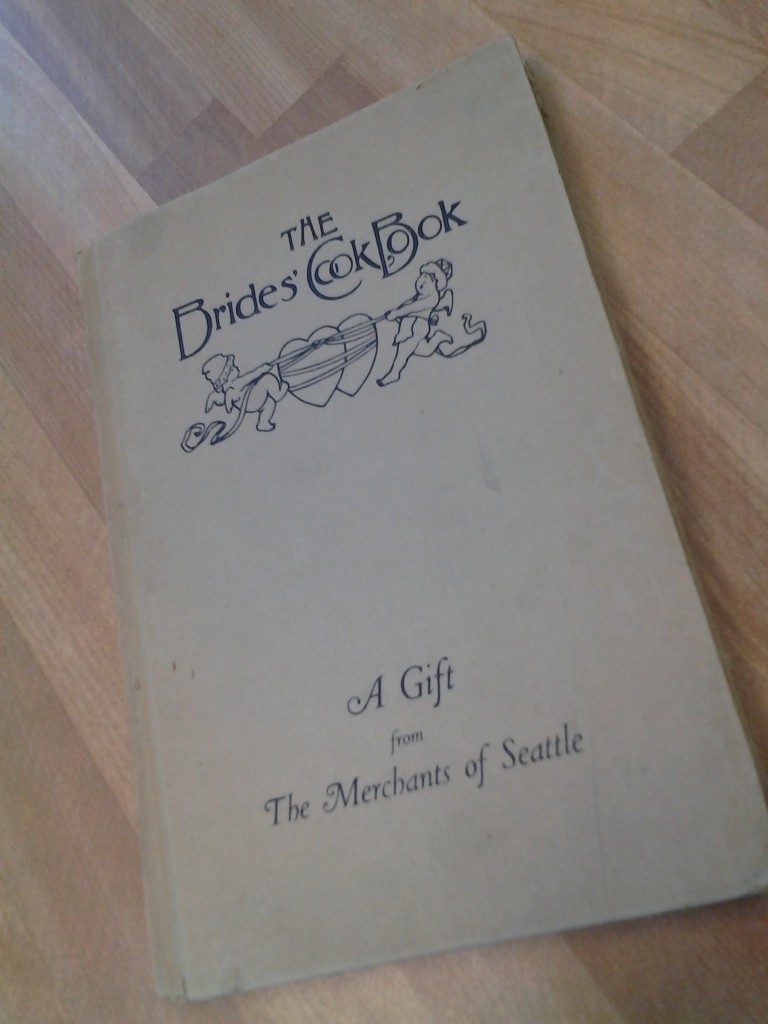

Flour hoarding was considered a crime in the United States during most of 1918 as the country mobilized for the Great War. The U.S. Food Administration apparently was seen as the enforcement agency. One curious publication in the WSL collection from this era is The Bride’s Cook Book, which takes wartime food rationing into account. A USFA official writes in the preface, “By following the Wheatless and Sugarless recipes contained therein the Housewife is performing a patriotic duty in the conserving of Food so necessary for our Allies and armies abroad.”

Flour hoarding was considered a crime in the United States during most of 1918 as the country mobilized for the Great War. The U.S. Food Administration apparently was seen as the enforcement agency. One curious publication in the WSL collection from this era is The Bride’s Cook Book, which takes wartime food rationing into account. A USFA official writes in the preface, “By following the Wheatless and Sugarless recipes contained therein the Housewife is performing a patriotic duty in the conserving of Food so necessary for our Allies and armies abroad.”

Pierre Peyre Ferry (1868-1932) was a successful Seattle attorney and capitalist. Here’s a WSL connection: his brother, James Peyre Ferry (1853-1914), had served as Territorial Librarian 1880-1881.

The Pierre P. Ferry house, scene of the crime, still stands today and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. I believe it was listed in spite of the flour caper, not because of it.

[Ferry portrait from: The Cartoon : a Reference Book of Seattle’s Successful Men (1911)]