Random News from the Newspapers on Microfilm Collection: James Fitzgerald, the Human Ostrich

Random News from the Newspapers on Microfilm Collection: James Fitzgerald, the Human Ostrich

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

“No, sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

I was reminded of this quote from the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance after breezing through several old newspaper articles regarding the life and adventures of James Fitzgerald, who was known on both sides of Washington State as “The Human Ostrich.” The facts are very inconsistent from story to story, but each story makes fascinating reading.

It all started when the microfilm reel I grabbed at random for this installment turned out to be the White Bluffs Spokesman, from the now extinct town of White Bluffs. Somehow it seems fitting to this story the town had the word “Bluffs” in it, as we shall see. This article was on the top of the fold for the February 18, 1916 issue:

Human Ostrich Checks Out

“James Fitzgerald, once a resident of White Bluffs, and who became notorious after he left here by eating considerable glassware and a hardware store or two, is dead. He was 69 years old and his death occurred a short time ago in the county hospital at Prosser, of dropsical complications.”

“Fitzgerald was a man of unique appearance, being six feet and six inches tall. He had a double set of teeth and could chew glass as easily as most people chew gum.”

“He was operated on in Seattle a few years ago and something like 50 different articles were taken from his stomach. The list included knives, nails, pieces of glass and one ten dollar gold piece. For a time before his death, this ‘human ostrich’ was the star attraction at the Gibbs moving picture show in Richland.”

Both of the Prosser papers covered Fitzgerald’s death. The Independent Record and its rival The Republican-Bulletin repeated the Human Ostrich story, as well as the double set of teeth. But both added that Fitzgerald had been living in the east end of Benton County for several months and had been in ill health for awhile. Also, he had worked in the circus. The latter paper had additional information: Fitzgerald was born in Ireland, and “In his younger days he is said to have traveled with circuses and museums.”

The ten dollar gold piece found earlier in Fitzgerald’s stomach was also mentioned by The Republican-Bulletin: “At the time the operation was made the surgeon doing the work offered his services free if Mr. Fitzgerald would give him what he found. Fitzgerald, however, demurred at this arrangement insisting that he should be allowed to retain the gold piece, and the matter was adjusted in that way.”

As it turns out, Fitzgerald had been the subject of an operation only a few months before, not years, in May, 1915. He died January 17, 1916, apparently having never fully recovered from the surgery.

According to the 1910 census from King County in the appropriately named Novelty Precinct, Fitzgerald was born in Ireland and arrived in the United States in 1884. He was 62 years old in this census, working as a railroad section hand. He never married.

There were several acts in United States history billing themselves as “The Human Ostrich,” performers who could consume anything and did, for a price. It is possible Fitzgerald was the true identity of “The Original Human Ostrich” who was an attraction at Seattle’s Luna Park starting in 1907.

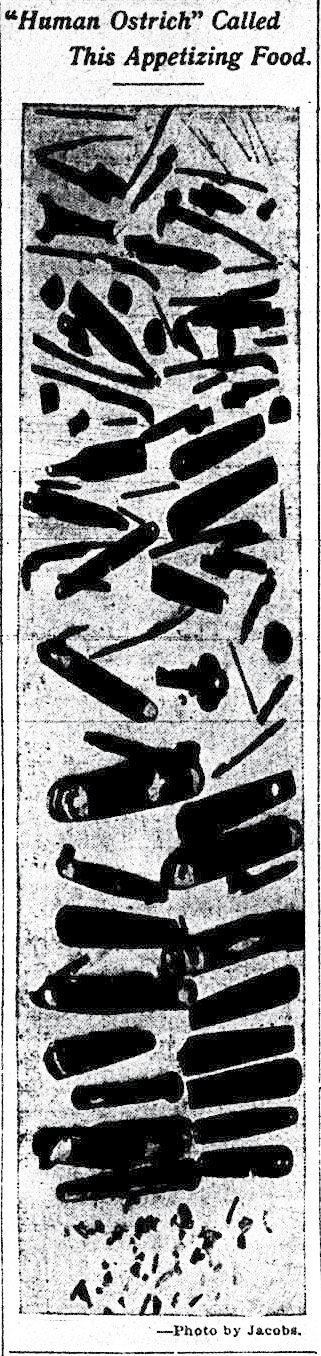

On May 1, 1915 the Post-Intelligencer took The Human Ostrich under its wing (get it?) when the paper ran a long feature article on Fitzgerald after the surgery which resulted in the removal of over a pound of metal and glass debris from his stomach. He told the press he had stopped eating nonfood items a couple years earlier, but didn’t start experiencing severe pain until recently. According to the P-I, the following items were retrieved from the patient’s stomach:

8 knives

1 bolt, two and a half inches long, with a nut on the end

1 dime

1 penny

1 nickel

1 shoemaker’s awl

1 loaded 30-30 Krag-Jorgensen cartridge

1 key

5 pins

9 parts of jack-knife handles

11 knife blades

9 flat springs

4 German silver ring tags

3 nails

100+ bits of broken glass

A photo displaying these items accompanied the news piece. The article did not mention a ten dollar gold coin.

Fitzgerald told the paper he discovered he could eat almost anything without ill effect in 1885 while in Quincy, Illinois. Despondent and unemployed at the time, he ate rocks and shingle nails, hoping it would kill him. But not only did he live, he didn’t suffer any discomfort. He appeared to have made a living out of making bets in taverns based on what he could or could not eat. It is probably safe to assume a goodly amount of alcohol was a major contributing factor in these wagers.

The story said he had lived in Seattle since the late 1890s, “occasionally working in the lumber camps or mines.” The reporter mentioned Fitzgerald’s “rich brogue” and described his subject as “a brawny, big-framed two-fisted man, who stands more than 6 feet tall in his stocking feet and weighs nearly 200 pounds.” No mention of the double set of teeth, although this was included: “With considerable relish Fitzgerald yesterday told how easy it was to eat a beer glass if one were careful about biting off the chunks and to chew them thoroughly. That the habit is not more general seemed strange to Fitzgerald, who was obviously of the opinion that any person could do it who had ambition and the appetite.”

A follow-up P-I article on May 25 explained how Fitzgerald had become a national celebrity in the medical community. Dr. Don H. Palmer was the operating surgeon. The King County Medical Society wanted the patient to appear before them for more examination and questions.

It would seem Mr. Fitzgerald never quite recovered from the surgery. He died less than a year later, and is buried in Prosser’s Odd Fellows Cemetery. I could make another wordplay here, but that would be in bad taste. (That was a double-score two-in-one-sentence set of puns in that last line!)

White Bluffs, the town hosting the newspaper article that started this whole little trail, ceased to exist in 1943, when the federal government took over the area as part of establishing the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Exactly when, why and how long Fitzgerald lived there is unknown.

If you have any information on this interesting character in Washington State history we would love to hear from you.