From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library

From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library

Do you believe in water witchcraft? The following article was found in the October 15, 1891 issue of the Big Bend Empire, from, appropriately enough, Waterville, Washington. A small chunk of the article is missing so I have tried to transcribe this around it.

Water Witches

“Witches used to be held in fear and abhorrence, in the olden times. People suspected of dealing in the supernatural were persecuted and put to death. A familiar test, which was inflicted upon those falling under the ban of suspicion, was the ducking stool, which was a see-saw contrivance, with a chair at one end in which to seat the victim, securely tied. The loaded end projected over a pond, and the chair and its occupant were soused into the water, in order to determine by the cries and struggles of the half-drowned wretch, whether she was witch or not. An ability to take water with composure was the test. What a number of condemned would there be nowadays, were the same tests applied.”

“Perhaps this enforced familiarity with water, may have descended to later generations of dealers in the mysterious. Be that as it may, witches, so called, are not unusual figures in the wonderful country of the Big Bend of the Columbia, and most singular of all, they are in demand. Many honest grangers have dug and dug for water on their claims, in locations of their own choosing, scouting the idea that the efforts of water witches were anything but nonsense. A majority of these unbelievers after sadly depleting their pockets in vain endeavors to strike moisture, at last come reluctantly to the point of trying the water witch.”

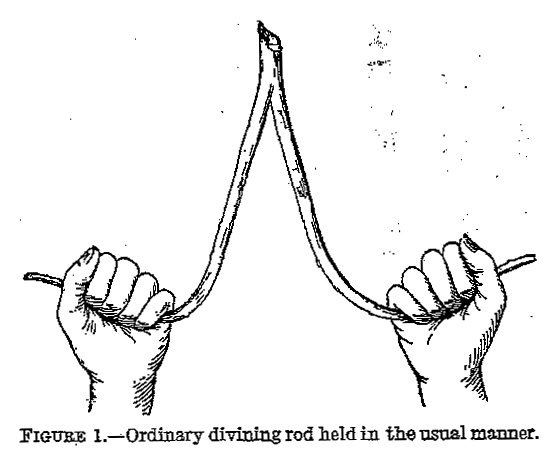

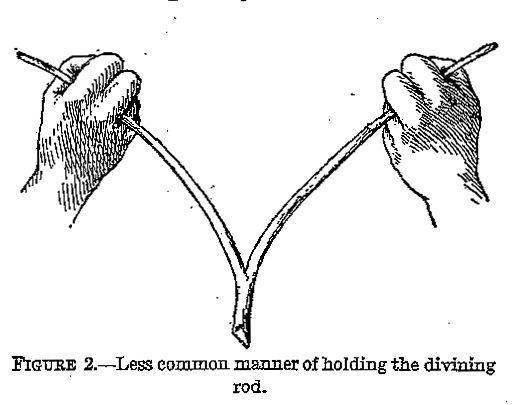

“With his cabalistic stick held in both hands, the magnetic individual struts across fields indicating the course of veins  and pointing out the proper place to dig. He even tells within a foot or so, just how far down the well must be sunk before water is reached. The witch claims nothing supernatural about his work. He says it is electricity. As he goes over the ground, when passing above a vein of water, his stick visibly turns and points out the location of the underground stream. It is simple enough. He holds the magnetic stick and it does the rest. […]over this phenomenon may be […]d dozens of settlers will tes-[…] finding water through such a […] Some of the so-called water witches have never been known to fail, […] confident of their powers are they, that they contract to pay for the cost of digging, if their location proves a barren one. Often 60 or 70 even 100 feet down do the diggers go, the witch indicating beforehand the depth to which his guarantee runs, and paying for the work in the event of failure. If he succeeds he gets $5.”

and pointing out the proper place to dig. He even tells within a foot or so, just how far down the well must be sunk before water is reached. The witch claims nothing supernatural about his work. He says it is electricity. As he goes over the ground, when passing above a vein of water, his stick visibly turns and points out the location of the underground stream. It is simple enough. He holds the magnetic stick and it does the rest. […]over this phenomenon may be […]d dozens of settlers will tes-[…] finding water through such a […] Some of the so-called water witches have never been known to fail, […] confident of their powers are they, that they contract to pay for the cost of digging, if their location proves a barren one. Often 60 or 70 even 100 feet down do the diggers go, the witch indicating beforehand the depth to which his guarantee runs, and paying for the work in the event of failure. If he succeeds he gets $5.”

Interestingly, 70 years later the periodical Northwest Science pointed out (v. 35, issue 4, 1961): “the number of water witches is greatest where chances are smallest that any one well will be successful. They state that in the Columbia Plateau the ratio of witches to population is the highest in the United States. The reason is not that water is scarce, but rather that the permeability of the Columbia River Basalt is extremely variable. A well that yields large quantities of water can be drilled within a few tens of feet of a well that was a dry hole.”

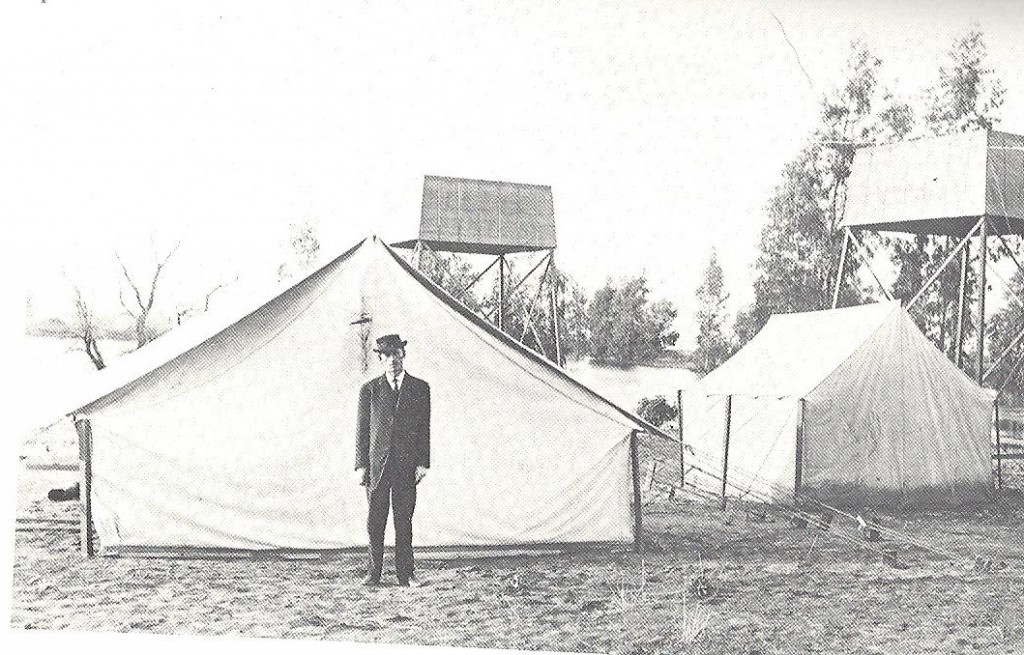

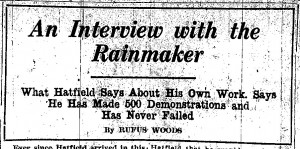

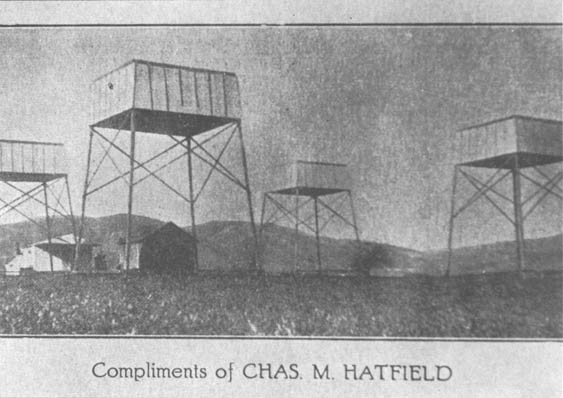

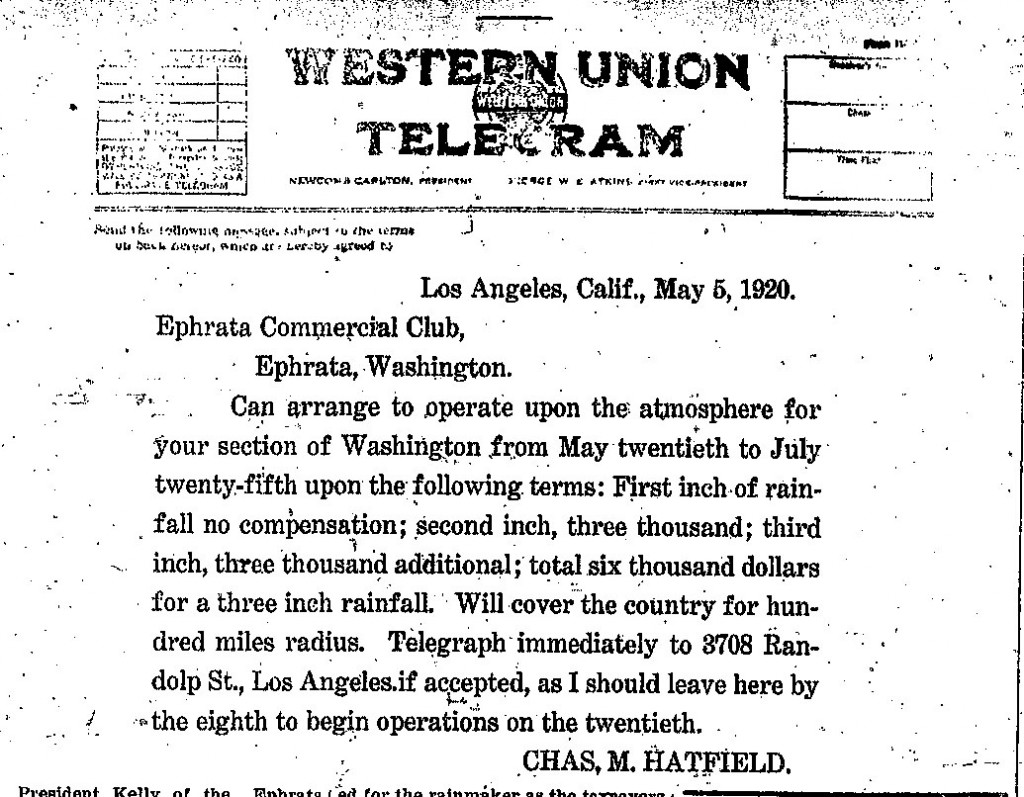

Adequate water supply was more important than gold to many of the residents in the Columbia Plateau. Some of our readers might recall the post we ran awhile back, also from the Big Bend Empire, regarding the rainmaker Charles Hatfield visiting the area in 1920.

Water witching, also known as dowsing, has been around for a long time but has never been fully accepted as a legitimate tool by the scientific community. The Dewey Decimal classification system places dowsing in 133.323 in the neighborhood of fortune-telling, parapsychology and occultism.

Water witching, also known as dowsing, has been around for a long time but has never been fully accepted as a legitimate tool by the scientific community. The Dewey Decimal classification system places dowsing in 133.323 in the neighborhood of fortune-telling, parapsychology and occultism.

A federal publication entitled The Divining Rod : a History of Water Witching, With a Bibliography / by Arthur J. Ellis for the US Geological Survey, originally published in 1917, is pretty blunt: “It is doubtful whether so much investigation and discussion have been bestowed on any other subject with such absolute lack of positive results. It is difficult to see how for practical purposes the entire matter could be more thoroughly discredited, and it should be obvious to everyone that further tests by the United States Geological Survey of this so-called ‘witching’ for water, oil, or other minerals would be a misuse of public funds.”

As late as 1977, in the publication Water Dowsing, the Feds would write: “Despite almost unanimous condemnation by geologists and technicians, the practice of water dowsing has spread throughout America. It has been speculated that thousands of dowsers are active in the United States; many are members of the American Society of Dowsers, Inc.”

But a brief walk through Internet will demonstrate that dowsing is as strong as ever, and just as controversial now as it was in 1891.