From the desk of Steve Willis, Central Library Services Program Manager of the Washington State Library:

The fun part about murky plots and conspiracies is that they are just that– murky, leaving a mystery for historians to argue about for decades. Even at the time the daring plan of Confederate agents in Victoria B.C. to capture a Port Townsend-based Revenue Cutter was exposed, rival newspapers could not agree on the facts of the case.

The following article was found in the March 7, 1863 Washington Statesman, a Walla Walla newspaper. John T. Jeffreys was apparently remembered in that city as “Sensation John,” from his exploits in the area serving as a lieutenant with the Oregon Volunteers during the Native American conflict of 1855-56.

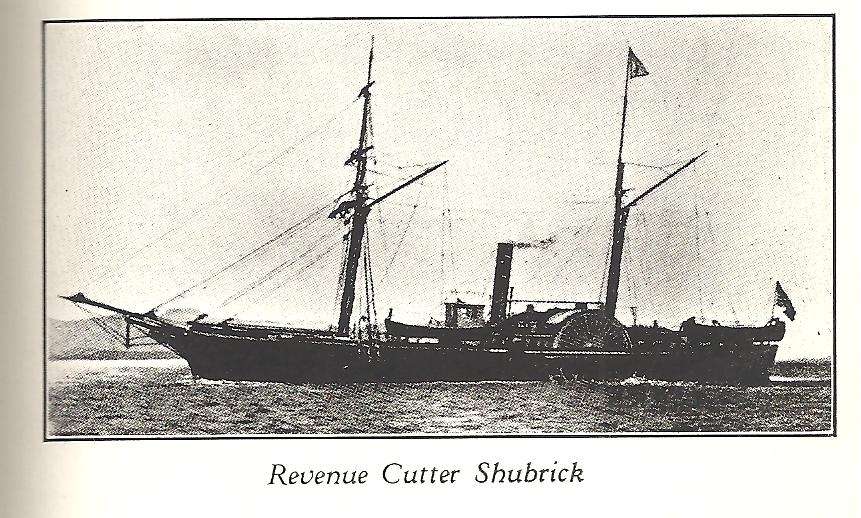

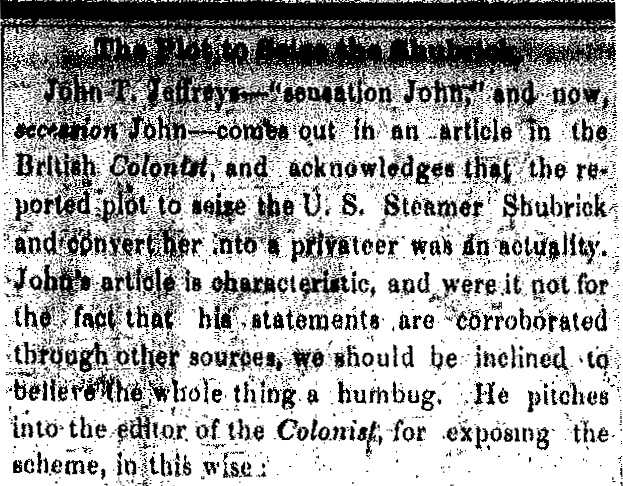

The Plot to Seize the Shubrick

“John T. Jeffreys– ‘sensation John,’ and now, secession John– comes out in an article in the British Colonist, and acknowledges that the reported plot to seize the U.S. Steamer Shubrick and convert her into a privateer was an actuality. John’s article is characteristic, and were it not for the fact his statements are corroborated through other sources, we should be inclined to believe the whole thing a humbug. He pitches into the editor of the Colonist, for exposing the scheme, in this wise:”

“‘I admit freely that there was a Confederate Commodore here, and that he had a commission in his pocket. I admit that a crew was picked and that the object was to injure Federal commerce in these waters. In short, I admit everything that you have stated, except that the expedition was a piratical one, and that the design was to burn the mail steamer. That would never have been done, except in case of necessity, which, I think is safe to say, would never have arisen.'”

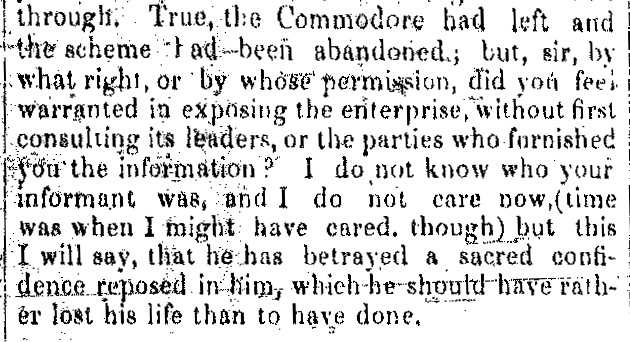

“‘I make this statement boldly, not because I wish to render myself notorious, but because you have meanly– with a meaness which your friends never supposed you capable of– violated a confidence reposed in you, and made an affair public which you should have kept locked within your own breast. True, the thing had fallen through. True, the Commodore had left and the scheme had been abandoned; but, sir, by what right, or by whose permission, did you feel

warranted in exposing the enterprise, without first consulting its leaders, or the parties who furnished you the information? I do not know who your informant was, and I do not care now, (time was when I might have cared, though) but this I will say, that he has betrayed a sacred confidence reposed in him, which he

should have rather lost his life than to have done.'”

“Pity that this betrayer of ‘sacred confidence’ did not have the power to do it in such a manner as to have had the plotters ‘left dangling at a rope’s end.'”

Identified by some as an Alabaman, John Thomas Jeffreys was actually born in Independence, Missouri April 7, 1830. John, along with his parents and siblings, went overland by wagon train to northwest Oregon in 1845. After the 1849 death of their father Thomas Jeffreys, the family moved The Dalles.

John was in the cattle trade and along with his brother Oliver found an excellent market in British Columbia. According to F.W. Laing in the Oct. 1942 British Columbia Historical Quarterly, the brothers Jeffreys first show up in BC documents as early as 1860. Benjamin F. Gilbert in the July-Oct. 1954 issue of the same periodical has a long essay on the details of Jeffreys’ involvement in the Shubrick case.

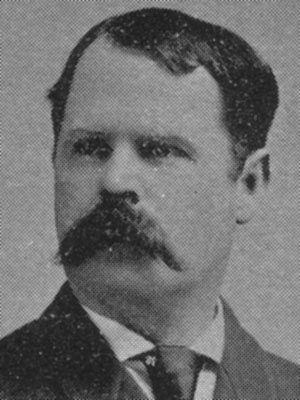

The newspaperman who Jeffreys felt betrayed him was actually with the Victoria Daily Chronicle. His name was David Williams Higgins and he later wrote a memoir suggesting the plot was really exposed by Union intelligence rather than by journalists. According to Scott McArthur in The Enemy Never Came, the American Consul Mr. Francis informed the Shubrick’s pro-Union second in command, Lt. James M. Selden, of the plot. Apparently the skipper and other sailors were in on the plan. So when the Shubrick visited Victoria “while the ship’s captain and most of the crew were ashore, Selden and six members of the crew cast off and returned to Port Townsend.”

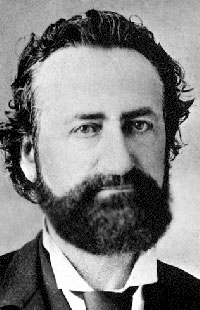

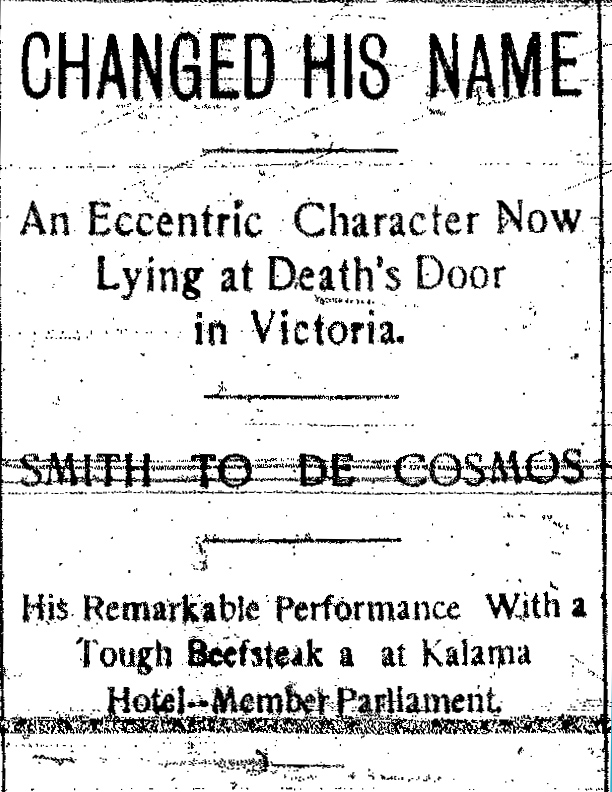

The rival Victoria newspaper, The Daily British Colonist, was openly critical of the Chronicle for being sensationalist and a scandal sheet. The publisher was none other than that steak-juggling eccentric, Amor de Cosmos, who we met in an earlier post. De Cosmos had been Higgins’ mentor and employer before the two had a falling out in 1862.

Shortly after the Shubrick incident Jeffreys returned to Oregon, where he was arrested. He died in The Dalles Feb. 24, 1867, aged 36.

The Shubrick continued life as a government ship until 1886, when it was sold in Astoria, Oregon and scrapped.

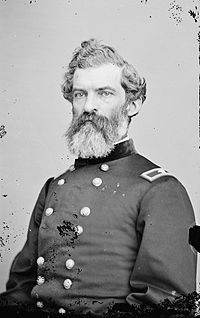

Maryland native Lt. James M. Selden was promoted to Captain in the U.S. Revenue Marine Service in 1867. He died March 16, 1888, aged about 57, as the result of sunstroke while on duty.

The Washington Statesman is available in online form thanks to the efforts of our Digital and Historical Collections team. It provides a window into Washington Territory’s contemporary view of the Civil War.

WSL also holds copies of the Daily British Colonist on microfilm.

David Williams Higgins (1834-1917) merged his own newspaper with the Colonist in 1866 to form The Daily British Colonist and Victoria Chronicle which he used as a springboard for political office.